Aerial view of the new university campus, 1938

Aerial view of the new university campus, 1938

Exhibit Gallery

by Barbara Floyd, 1997

Introduction

As a person grows older and taller in stature, the shadow he casts upon the earth grows longer. His impact on the world becomes more profound as he matures and succeeds. The same can be said of a university. The University of Toledo, created 125 years ago, has grown taller in stature and risen in influence. The shadow cast by its tower has lengthened.

This volume, The Tower’s Lengthening Shadow: 125 Years of the University of Toledo, is a scrapbook of the institution’s history. The 130 photographic images published here were selected from over 15,000 photographs preserved in University Archives. They visually tell the story of the university’s development from the small, private Toledo University of Arts and Trades in 1872 to its evolution as a municipal university from 1884 to 1967 and finally to its emergence as a large state university situated on several campuses providing educational opportunities to 20,000 students from around the world.

Many of the photographs published here were taken by unknown persons. Not only do many of the photographers remain anonymous, so too do many of the people shown in the images. If persons are unidentified or appropriate credit is missing, I apologize. Due to limitations on the size of this publication, unfortunately many important events and people had to be excluded. Still more are not included because no photographic image exists in the holdings of University Archives. The photographs that were selected seemed to summarize significant events or time periods in the university’s history.

There are many people to thank for their assistance with this publication and accompanying exhibit. First, special thanks to the members of the Friends of the University of Toledo Libraries. This group, which has been a part of the university’s history since 1936, generously provided the funding. Thanks to Sue Van Fleet and Jan Vezner of the Publications Office for their assistance with the design and production of the book and to Sue Benedict and Terry Fell from Audio Visual Services for assistance with the production of the exhibit. Much thanks to the staff of the Ward M. Canaday Center (especially Robert Shaddy and Janice Colwell) for their assistance, and to Leslie Sheridan, dean of University Libraries, for his editorial assistance with the manuscript. And a special thanks to Richard Perry for his comments on the manuscript and for his remarks at the exhibit opening.

And most importantly, thanks to the photographers—both known and unknown—who produced these remarkable images documenting 125 years of the University of Toledo.

—Barbara Floyd

University Archivist, University of Toledo

Chapter 1: The Early Years, 1872-1910s

Scott's reason for endowing the university was expressed in this pamphlet, first published in 1868, entitled "Toledo: Future Great City of the World." To fulfill its destiny, Toledo needed an institution to train its young people. Shown here is the title page of a reprint of the pamphlet's second edition. (The Blade Printing and Paper Company, 1937.)

Jesup Wakeman Scott, newspaper publisher and real estate broker, who donated 160 acres in 1872 as an endowment for the Toledo University of Arts and Trades.

In a small pamphlet published in 1868 entitled “Toledo: Future Great City of the World,” Jesup Wakeman Scott articulated a dream that led him to endow what would become the University of Toledo. Scott, who served as editor of The Toledo Blade from 1844-1847, often used his writings to promote the city. In this publication, he expressed his belief that the center of world commerce was moving ever westward, and by 1900 would be located in Toledo. The city would become bigger than Paris, London, or New York. To help realize this dream, in 1872 Scott donated 160 acres of land on Nebraska Avenue near a proposed railroad terminal as an endowment for a university to train the city’s young people to assume roles in the Future Great City.

Articles of incorporation were drawn up on October 12, 1872 for the Toledo University of Arts and Trades. The institution was to “furnish artists and artisans with the best facilities for a high culture in their professions....” Income from the lease of the Scott land, then valued at $80,000 but certain to increase rapidly when the railroad terminal opened, was to support the institution. The university was to offer its classes “free of cost to all pupils who have not the means to pay for the same, and all others are to pay such tuition and other fees as the trustees may require.”

Unfortunately for the struggling university, the railroad terminal never materialized. Jesup Scott died in 1874, a year before the university opened in the old Independent Church Building at 10th and Adams downtown. The building was named for trustee William Raymond, who gave the money needed to purchase it. The university’s curriculum centered on design courses, with painting and architectural drawing as the only subjects. The school was forced to close in 1878, however, because it was never able to gain appropriate finances.

Jesup Scott’s three sons—Frank, William, and Maurice—were disappointed by the failure of the school. They felt that the university might succeed if reorganized as a manual training school. But because they had no money, the sons turned over the university’s assets—including the 160 acres of land—to the city of Toledo on January 8, 1884. Three months later the city accepted the gift and agreed to use the assets to create a university, as was required by the Scott trust.

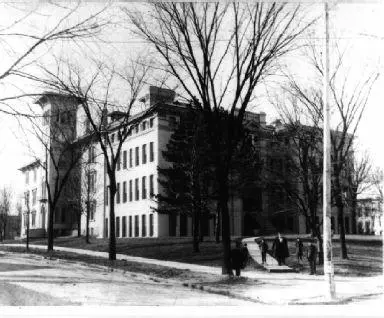

After being reestablished as the Toledo Manual Training School in 1884, the school moved into an annex of Central High School a year later.

The city ordinance accepting the assets stated that the school was to be called Toledo University, and its first department was to be the Manual Training School. A Board of Directors was appointed, and the Toledo Board of Education provided the top floor of the Central High School to house the Manual Training School. The school offered a three-year program for students at least 13 years old, who divided their time evenly between academic and manual instruction.

The Manual Training School was a huge success. Soon the school was out of room, and the Board of Directors asked the Board of Education to provide land for a new building. The ensuing disagreements between these two governing bodies were the first in a long line of fights which would not be resolved until 1911. But the new building was constructed as an annex to Central High.

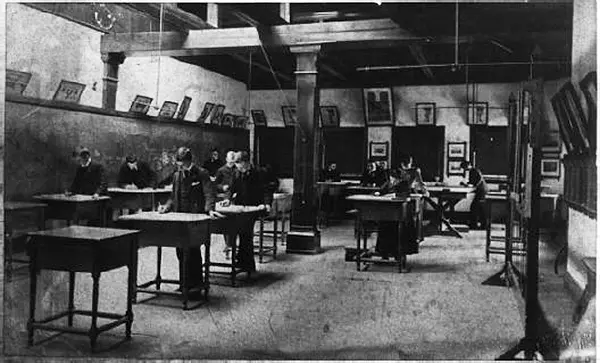

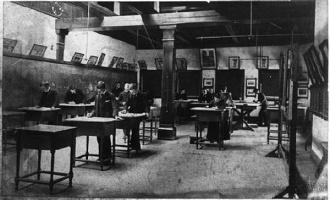

The Toledo Manual Training School offered a three-year program for students 13 years of age and older divided between academic and manual training.

Women were admitted to the school beginning in 1886.

A coeducational class in mechanical drawing at the Toledo Manual Training School, ca. 1890.

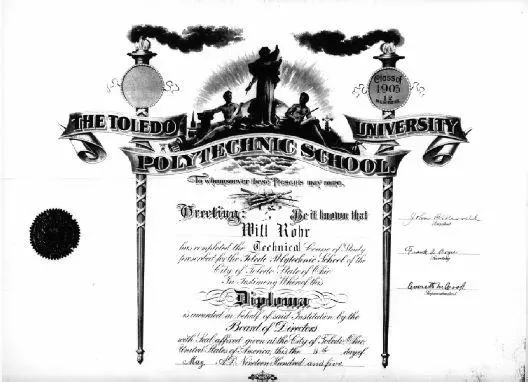

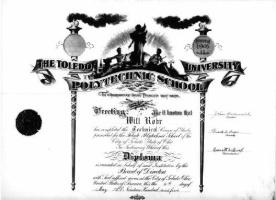

In 1900, the school changed its name to the Toledo University Polytechnic School, although most people still referred to it as the Manual Training School. Student Wi ll Rohr sued theBoard of Directors to gain admission when the directors decided to exclude students in the 8th and 9th grades due to a shortage of classroom space. Rohr was admitted, and he graduated in 1905.

Toledo University passed up a great opportunity in 1900. An anonymous donor offered to provide a substantial gift of money to turn the Manual Training School into a technical university. However, the Board of Directors turned down the offer because they felt it had too many strings attached. They learned after rejecting the gift that their would-be benefactor was steel magnate Andrew Carnegie. Carnegie gave his money a few years later for the establishment of the Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh.

The Manual Training School changed its name to the Toledo University Polytechnic School in 1900. However, most people continued to call it the Manual Training School, and it continued a curriculum of traditional and vocational instruction to students in the 8th grade and higher. Another quarrel broke out between the Board of Directors and the Board of Education over space for the school. When it could not be resolved, the Board of Directors decided to exclude students in grades 8 and 9 from attending. With this move, the battles between the two bodies intensified.

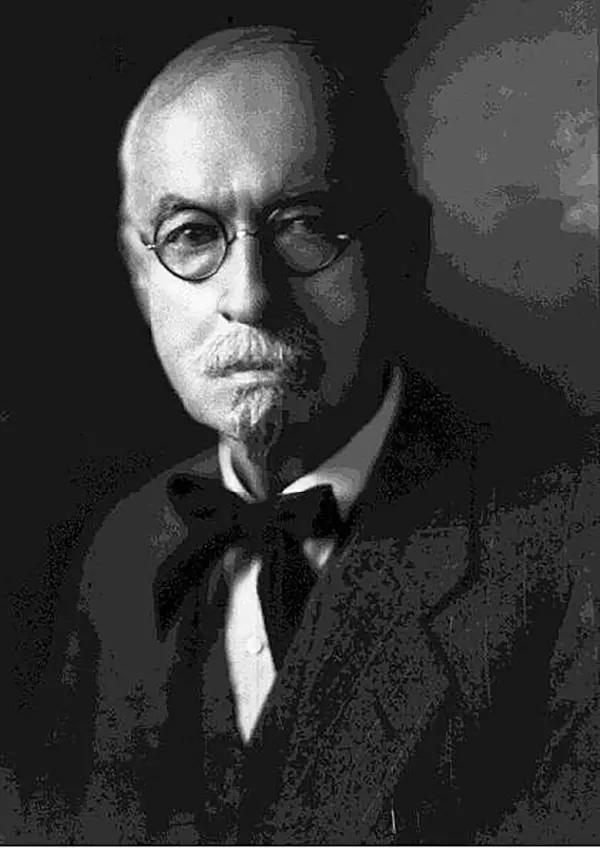

Albert E. Macomber, one of eight original trustees of the Toledo University of Arts and Trades, who became a vocal critic of the institution in the 1900s . (North and Oswald Photographers, Toledo , Ohio.)

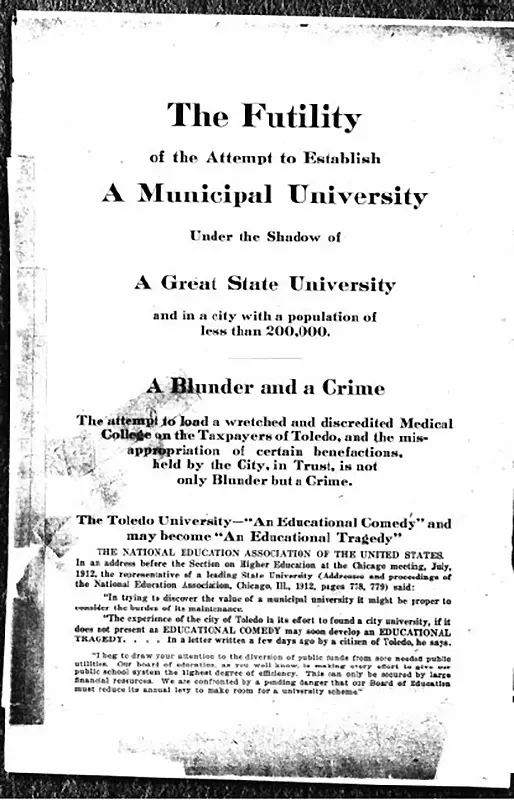

Albert E. Macomber, one of the original trustees of the institution in 1872 and an ardent supporter, suddenly turned on the school and began a lengthy battle against it. He sought to have the Polytechnic School abolished and reestablished as the manual training department of Central High. Maurice Scott supported Macomber because he felt the Polytechnic School was not the intention of his father’s original endowment.

The university’s Board of Directors needed a new facility to relieve overcrowding, and proposed selling the Scott farm property to pay for it. Macomber and the Scott sons sued, stating that the city and the Board of Education had no right to sell the land. The university’s Board of Directors turned to the state legislature, which in 1904 enacted legislation stating the right to regulate municipal universities was a power of city council, not the Board of Education. A circuit court ruling upheld the legality of the Board of Directors.

The battle between the two governing boards continued, and escalated. In 1905, the Board of Education refused to levy taxes to support the school, and the Manual Training School could not open for one month due to lack of funds. The next year the Board of Education sought to strengthen its hand by seizing the building that housed the school. Several members barricaded themselves inside, refusing to leave. The Board of Directors asked the city to file a lawsuit to finally settle the question of who controlled the university.

Jerome H . Raymond, first president of Toledo University, 1909-1910.

Funding for the school continued to be tenuous. In 1908, when the city tried again to levy taxes to support the institution, Macomber vigorously attacked the effort. He published a scathing circular criticizing the university. City government was unwilling to turn over any money to operate the institution until Board member Dr. John S. Pyle pointed out the city had just spent $2400 to purchase an elephant for the zoo. Surely, Dr. Pyle argued, the university was as important as an elephant. The tactic worked, and on June 15, 1909, the city granted $2400 to fund the institution. This did not end the financial problems of the university, however, and operating expenses often had to be made up out of the pockets of the directors.

Students gathered outside the entrance to the Toledo Medical College, Cherry and Page streets. The college affiliated with Toledo University in 1904.

Dr. Jerome Raymond was appointed the first president of the university in 1909. Despite the financial headaches and the on-going questions concerning the legality of the university’s existence, Dr. Raymond was able to make some progress for the university. He expanded the university’s offerings by affiliating with the Toledo Conservatory of Music and the YMCA College of Law and creating the College of Arts and Sciences. Along with its affiliation with the Toledo Medical College, which had occurred in 1904, these changes were important in moving the institution from being a manual training school to becoming an institution of higher education.

However, Dr. Raymond found the stress of the situation too much, and resigned in 1910. No candidates came forward to replace him because of the political difficulties and an annual city appropriation of only $3600. The university appointed Dr. Charles Cockayne, then on the faculty, as acting president.

Charles A. Cockayne, acting president from 1910-1914.

Undated class photograph taken in the operating amphitheater of the Toledo Medical College. The medical college was forced to close in 1914 when the American Medical Association issued new regulations governing medical education.

At this time, classes for the university were being held in both the Manual Training School facility and at the Toledo Medical College building at Cherry and Page. The Toledo Medical College building was nearly destroyed in a fire on January 9, 1911. This was a devastating blow for the directors. The university lost its laboratories, its library, and many classrooms. The directors were ready to give up and close the university. Fortunately, an arrangement was made to use the third floor of the Meredith Building at Michigan and Jefferson. The university continued to hang on.

One of the many pamphlets written by Albert Macomber criticizing the university. This one, published in 1913, said the Board of Directors extorted money from Toledo taxpayers for an unnecessary university that was little more than a diploma mill.

On January 24, 1911, in the case of Toledo v. Seiders et al., the university finally got the legal decision it had eagerly sought settling the questions of ownership and control. A circuit court decision (upheld by the Ohio Supreme Court) clearly established the legal existence of the university and the Board of Directors as its governing body. The city raised its budget to $5000, and for the first time it appeared the institution might survive.

The Board of Directors realized after the court’s decision that it no longer needed the Manual Training School. The curriculum did not fit with an institution that provided baccalaureate education. In 1914, the directors worked out an agreement to give the building to the Board of Education in exchange for an empty elementary school at the corner of 11th and Illinois. However, this building was not without its problems. It needed extensive renovation; it was in a bad neighborhood; and it was a mile from the Cherry and Page street building which, after having been repaired following the fire, continued as the location for many classes.

Allen R. Cullimore, acting president for five months in 1914.

With the new building came a new president. Dr. Cockayne was removed, although at first he refused to leave and his replacement, Dr. Allen Cullimore, had to change the locks on the president’s office door to keep him out. Dr. Cullimore served as acting president for five months until a permanent president, Dr. A. Monroe Stowe, took office on July 6, 1914.

Dr. Stowe faced many of the same challenges of his predecessors, and some new ones. In 1914, the Toledo Medical College closed, the victim of new regulations governing medical education issued by the American Medical Association. But despite this setback, Dr. Stowe seemed to have the vision to take the university on its first organized path of development. He established educational standards, admission requirements, and a formal curriculum. He founded the College of Commerce and Industry in 1914, and the College of Education in 1916. Enrollment grew from 200 students to 1400, and the budget increased to $200,000. Dr. Stowe took the first steps toward becoming accredited by the North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools, and in 1920 accreditation was granted.

The Board of Directors moved out of the Manual Training School building in 1914 to a renovated elementary school at 11 th and Illinois. This undated photograph shows many of the students gathered on the steps of the building.

A. Monroe Stowe, president of UT from 1914-1925.

Dr. Stowe’s tenure was not without controversy, however. In 1915, at the urging of Dr. Pyle, Dr. Stowe hired Scott Nearing as professor of economics and dean of the College of Arts and Sciences. Nearing was an economics professor who had been dismissed from the University of Pennsylvania for his radical views. With his national reputation, Nearing was sought after as a speaker, and came to be seen as the spokesperson for the working classes of Toledo. With the United States on the verge of entering World War I and the fear of Socialism on the rise, however, Nearing was attacked by many conservative groups in the city. They feared he was using his position in the classroom to teach Socialism to students. The groups and their influential leaders succeeded in getting Nearing dismissed from his position in 1917. His house was raided, many of his papers were confiscated, and the American Association of University Professors refused Nearing’s appeal for assistance.

Scott Nearing, a professor of economics and dean of the College of Arts and Sciences, was dismissed from his position in 1917 because some community leaders believed he was teaching Socialist ideas in the classroom.

Women also participated in the war effort. These women enrolled in an automobile mechanics class at the 11 th and Illinois Street building in 1917.

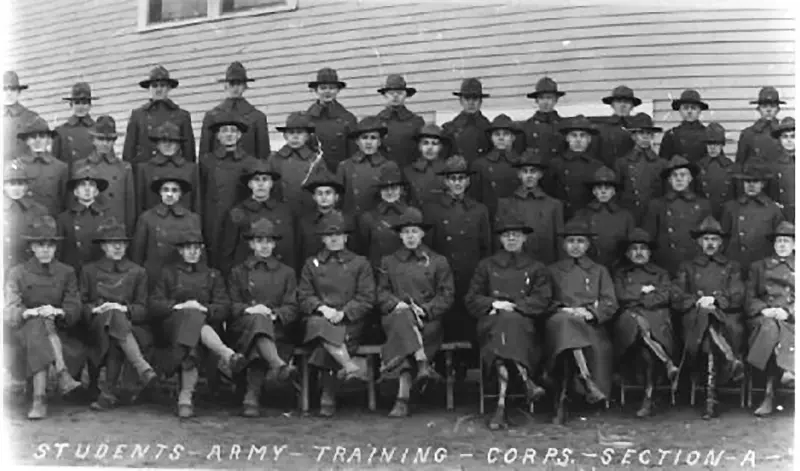

When the United States entered the war in 1917, enrollment dropped as students left to serve their country. The Committee on Education and Special Training of the U.S. War Department proposed a program to the university to train automobile mechanics for the war effort. A machine shop and dormitory were built on the Scott property on Nebraska Avenue for this purpose, as was housing for the Toledo University Section of the Students Army Training Corps. This program, the forerunner of ROTC, provided army training for many soldiers. Many of these students returned to the university after the war and enrolled as full-time students.

At the end of nearly 50 years of existence, Toledo University had emerged as a growing municipal university. While its critics, including Albert Macomber, continued to attack it, the institution had established the legality of its existence, had divorced itself from a manual training curriculum, and was accredited by a national agency. It continued, however, to be housed in several inadequate buildings, and in the next decade would be forced to find a permanent home.

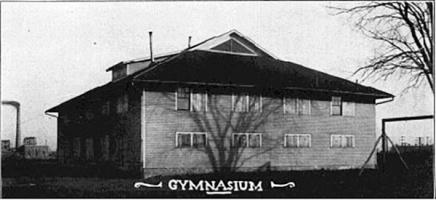

Students Army Training Corps in front of the Gymnasium on the Scott land, 1918. In 1918, the U .S. War Department created the Students Army Training Corps at colleges throughout the country to train young men for World War I. The Toledo University Section was housed in a dormitory building constructed on the Scott land on Nebraska Avenue. The building, seen here in the background, later became the Gymnasium when the university moved here in 1922. (Photo by Cull and Howard, 1918.)

Chapter 2. Finding a Permanent Home, 1920s-1930s

University Building on the Scott land on Nebraska Avenue in the 1920s. This building, partially constructed during World War I but never finished, was completed in 1922 as a classroom building for The University of Toledo. It was located on the Scott land at Nebraska Avenue. The university outgrew this building in less than ten years. By the 1920s, Toledo University was a growing institution, limited only by the buildings that housed it. Classes were held in the 11th and Illinois building and in the Toledo Medical College building at Cherry and Page. But with enrollments of 1500, not all students could fit into the auditorium; classrooms were crowded; and the library had to be used for classes and social events. New facilities were needed.

The first women's basketball team, 1922.

The buildings selected were the yet-unfinished automobile mechanics training facility and dormitory that had been constructed for the war effort on the original Scott land on Nebraska Avenue. With the U.S. role in the war so brief, the auto mechanics building was never completed and lacked floors, heating, and plumbing. City Council agreed in 1921 to spend $50,000 to complete that building as well as renovate the Students Army Training Corps dormitory located next door to it. While twice the size of the Illinois Street building, this location was less than ideal. It was hard to get to, was located in an industrial area, and looked like the factory it was intended to be. When renovations were completed, the university moved into the buildings in 1922, although classes continued to be held at the downtown buildings. The larger building was named the Science Building, and the dormitory was named the Gymnasium.

The Students Army Training Corps dormitory building, also located on the Scott land, was renovated as the Gymnasium in 1922.

As further evidence that the university was maturing, student participation in extracurricular activities increased. Student Council was created in 1919 as the governing body of the student population. Also that year, students Samuel Steinback and Leo Steinem started a student newspaper called The Universi-Teaser, which they sold for five cents. The newspaper staff also initiated a yearbook, called The Blockhouse, which was published in 1922. Greek organizations proliferated on college campuses in the 1910s, and their growth at UT led to the creation of the Pan-Hellenic Council in 1920 to oversee the groups. Deans of men and women were also appointed to assist with these student organizations.

Members of the Kappa Pi Epsilon sorority, 1922.

In 1915, the students had petitioned the Board of Directors for an intercollegiate athletic program. Football started in 1917, although the first game was a 145 to 0 loss to the University of Detroit. The basketball team fared better, losing only two games in 1919. The sports program progressed to the point that O. Garfield Jones, a professor of political science, was appointed the first part-time director of athletics. The sports teams received their nickname, the Rockets, in 1923 from local newspaper writers who thought the name reflected the teams’ style on the playing field.

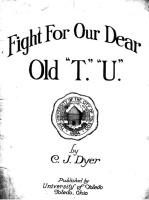

The University of Toledo's fight song, "Fight for Our Dear OU:! T. U.," written by C.J. Dyer in 1922

In 1921, the university itself got a new name. President Stowe wanted a name that clarified the relationship between the university and the city in order to help the institution gain accreditation by the North Central Association. The city agreed to change the name to the University of the City of Toledo, which was shortened to the University of Toledo in 1941.

Dr. Stowe made an important improvement to the institution in 1917 when he created a real library and appointed a librarian. Prior to that time, the university had been using the city library. Despite this and other efforts to improve the institution and create a mature university, President Stowe began to have disagreements with the faculty and students. He resigned his position in 1925. Hard feelings remained between the Board and several faculty members who had disliked Dr. Stowe, and it was left to the new president, John W. Dowd, to mend fences.

John W. Dowd, president from 1925-1926.

President Dowd, who was 78 years old when appointed, served as president for only 14 months before he died. The next president, Ernest Ashton Smith, had an even shorter tenure, serving less than two months in 1927 when he died of a heart attack. During the interim periods between presidents, Dr. Lee MacKinnon served as acting chief administrator.

Lee W. MacKinnon, who served as chief executive during two interim periods following the deaths of John Dowd and Ernest A. Smith, 1925-1928.

The limitations of the Nebraska campus soon became evident. Despite being twice the size of the Illinois building, it was not big enough. An enrollment increase of 32 percent in one year made the situation critical. The space problem was exacerbated when a female student returning from classes at the Illinois building was beaten to death, and it became clear that this downtown neighborhood was too dangerous. The building located there would have to be closed. In November 1926, City Council appointed a subcommittee to consider a new site for the university.

Students participated in the campaign to gain passage of the bond levy for a new university campus in 1928.

President Henry J. Doermann at the groundbreaking for the new University of Toledo campus on Bancroft Street, 1929.

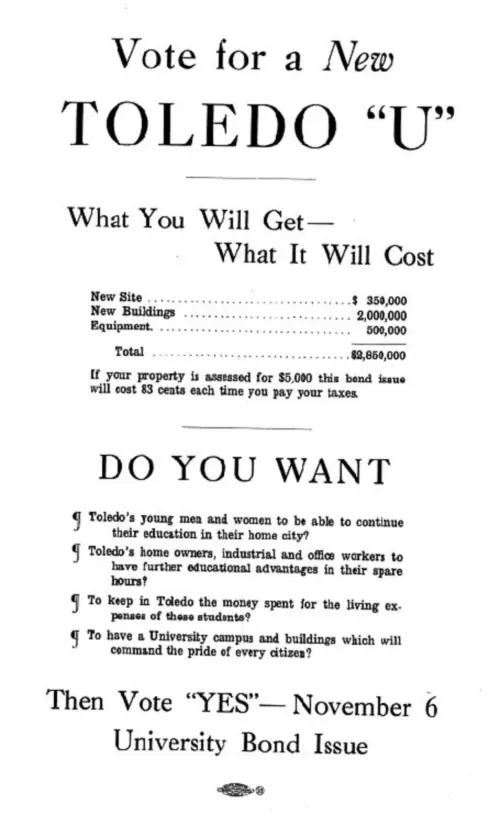

One of the circulars distributed to Toledo taxpayers to win support for the bond levy. It stressed that a new university would cost the average taxpayer less than $1 in new taxes.

The prospects for a new, permanent home for the institution improved in 1928 when the Board selected a new president, Dr. Henry J. Doermann. His first activity upon arriving in Toledo from Puerto Rico, where he had been university chancellor, was to plan for a new campus. He hoped to pay for the new campus by selling the Illinois, Cherry and Page, and Scott Park buildings. But legal difficulties held up the sale, and the city decided instead to place a bond levy before the voters to raise between $2.5 and $3 million. An all-out campaign orchestrated by O. Garfield Jones with the help of nearly all students and faculty led to the levy’s passage by 10,000 votes. The taxpayers’ approval came less than a year before October 29, 1929—Black Monday—and the start of the worst economic depression of modern times. A levy campaign in November of that year might not have been successful, and the university’s future would have been much bleaker.

With the money appropriated, the city began the search for a site for the new campus. Ottawa Park and Detweiler Park were among the 34 proposed locations. One attractive site was the Rufus Wright farm on West Bancroft. At a public hearing to consider the matter, Albert Macomber, then age 92, rose to speak. Rather than criticize the plans for a new campus, however, Macomber surprised all by supporting the move and suggesting that the Wright farm was the best site. An outside consultant agreed because it was centrally located, easily accessible, and located in a pleasant residential neighborhood. The 80 acres were purchased for $275,000.

The cornerstone for University Hall was put in place at a ceremony during commencement on June 12, 1930. President Henry Doermann spoke at the event.

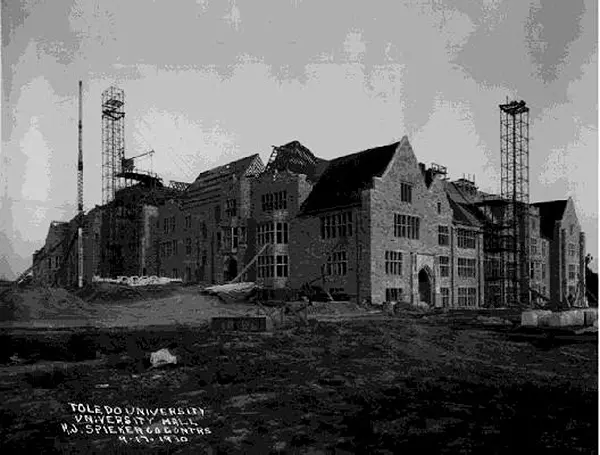

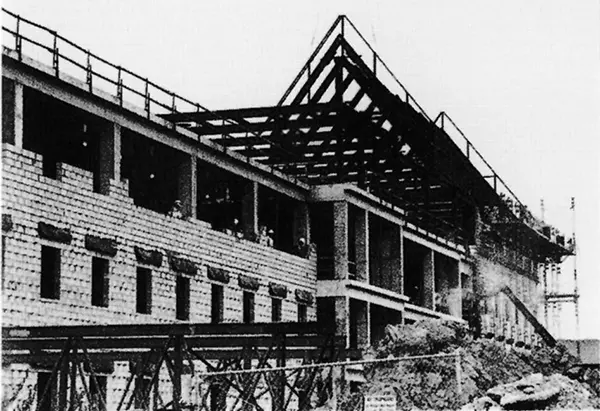

Progress on the construction of University Hall in 1930 is shown in these photographs from the Henry J. Spieker Company, the contractor for the project.

The local architectural firm Mills, Rhines, Bellman, and Nordhoff was selected to design a classroom building and a multipurpose building for the site. Dr. Doermann wanted the buildings to reflect the best design elements of the old universities of Europe because he felt such architecture would provide an atmosphere to inspire students. A Collegiate Gothic design with a central tower and two enclosed courtyards was chosen for the classroom building, despite the objections of many Toledoans who felt the design was too extravagant. The Henry J. Spieker Company received the construction contract.

The cornerstone-laying ceremony coincided with commencement in 1930. It took 400 men eleven months to complete University Hall and the Field House. When the buildings were finished, President Doermann held a five-day open house in February 1931 for the taxpayers of the city, and 60,000 came to tour the new campus.

Some 400 men worked eleven months on the construction of University Hall and the Field House.

The theater in University Hall as it looked when completed in 1931. It was named in honor of President Henry Doermann following his sudden and unexpected death at the age of 42 in 1932.

The new campus was about all the citizens of Toledo had to cheer about in 1931. Toledo was hit hard by the depression, with a larger percentage of its population in bread lines than any other city in the nation. City workers took a ten percent pay cut, and the faculty voted unanimously to join them. This would be the first of four such cuts, not to mention several months when faculty were not paid at all, or were paid in “scrip.” Tuition was raised slightly for students taking more than 12 hours, up to $2 per credit hour.

Despite these difficulties and a career cut short by his untimely death, President Doermann realized some successes during his tenure as president. He capitalized on the tie between Toledo, Ohio, and Toledo, Spain, by forming a sister city relationship between the two cities. To reflect this relationship, the new university seal had the words “Guide to the Present, Moulder of the Future” written on it in old Spanish, rather than the more traditional Latin. In addition to planning the new campus and presiding over an institution during an economic depression, Dr. Doermann found time to direct a theatrical production of Hamlet in the new university theater in 1931. When he died suddenly in 1932, the theater was named in his honor.

May Day celebrations were an important student event. Pictured here is May Day,1930 .

Following an interim period presided over by Lee MacKinnon, the Board appointed Philip C. Nash as president in 1933. Dr. Nash had been dean of Antioch College and executive director of the League of Nations Association, a group that supported U.S. participation in the League. World affairs remained an interest throughout his life.

While enrollments remained stable at UT during most years of the Depression, due primarily to students from wealthier Toledo families who were forced to remain at home rather than go to Eastern colleges, the university’s financial situation was dire. President Nash instituted drastic measures to cut costs, including eliminating faculty phones, canceling the university catalog, and prohibiting faculty travel. The Board appropriated $3500 for special scholarships to help poor students attend the university. Additional funds came from the federal government, allowing students to pay for tuition by working at on-campus jobs.

Construction of Scott, Tucker, and Libbey Halls began in 1934, and was another project funded by the federal government's New Deal programs

The government’s New Deal programs provided other opportunities for federal funding for the university. Three faculty and student housing units (Scott, Tucker, and Libbey halls) were constructed with a federal loan and grant in 1934. The Works Progress Administration granted a contract in 1936 to build an 8000-seat stadium that kept many Toledo men employed. Funds from the Public Works Administration financed MacKinnon Hall, a women’s dormitory, in 1938. Artists working for the Civil Works Administration painted the seals of the alma maters of UT faculty on the walls of the third floor of University Hall and murals of Toledo history on the walls of the library. Another grant from the Works Progress Administration paid for the demolition of the Toledo Medical College building at Cherry and Page.

A football stadium was constructed by workers employed by the Works Progress Administration in 1936. Most of the work was done with shovels and wheelbarrows.

A community effort began in 1936 to help the UT library. With the assistance of the Toledo Chapter of the American Association of University Women, the Friends of the University Library was created. The group was similar to one that Philip Nash had known at Harvard. Its efforts especially were needed after a survey by the North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools revealed that Toledo’s library was inadequate. Among the group’s activities was soliciting the donation of books from Toledo residents for the library.

The university library on the fifth floor of University Hall as it looked following the completion of historical murals by artists with the CWA, ca. 1940. (Photograph by Edward O'Reilly.)

When the Depression decade came to a close, the University of Toledo not only had survived, but in many ways had prospered. Thanks to the foresight of President Henry Doermann and federal funds made possible through the agencies of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, the university had a new campus. Enrollments remained stable, and those students who attended during the decade felt a special closeness wrought by difficult times. Despite several months when the payroll could not be met, President Nash managed to keep the university out of the red. But the next decade would bring many more challenges to Dr. Nash, the student population, and the university.

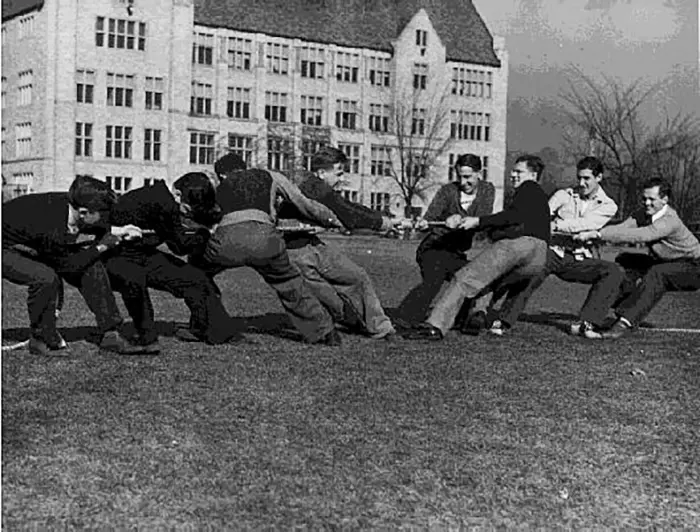

A friendly game of tug of war, 1939.

Football coach Clarence "Doc" Spears, 1939.

The University of Toledo baseball team with coach David Connelly, ca. 1939.

Aerial view of the new university campus, 1938

Chapter 3. The War and Its Effects, 1940s-1950s

The Depression decade was one of the most challenging for the University of Toledo. Despite the optimism brought by a new campus, the economic devastation of the city led some in Toledo to question whether the money spent on the university might not be better spent elsewhere. Many students who attended UT were so destitute that the most sought-after campus job was in the cafeteria because it provided a free meal each day. But for the students who were able to attend, the university provided them an opportunity for a better future.

President Philip C. Nash (1933-1947) saw the university through much of the Depression and all of World War II.

While the Depression decade determined in many ways if the university would survive, it was World War II and its aftermath that was the real watershed. The war transformed UT from a small, tenuous municipal institution barely able to make ends meet into the modern university it is today. Everything was changed by the war: the students, the faculty, the curriculum, and the social life. Some students who dropped out to fight for their country never returned. Thousands of others who never considered a college education found that military service provided them the opportunity that was previously beyond their reach. Some faculty left their teaching positions for government research jobs. Those who remained often had to fill in and teach courses outside their specialties. New programs of study included pilot training and military nursing. Campus social activities changed from dances and parties to holding war bond drives and knitting bees.

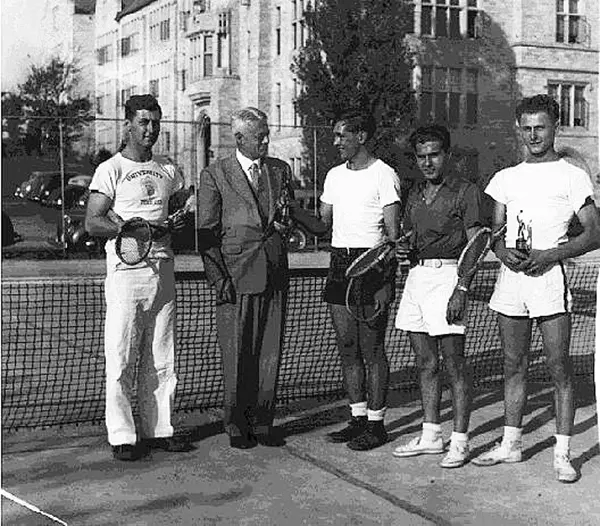

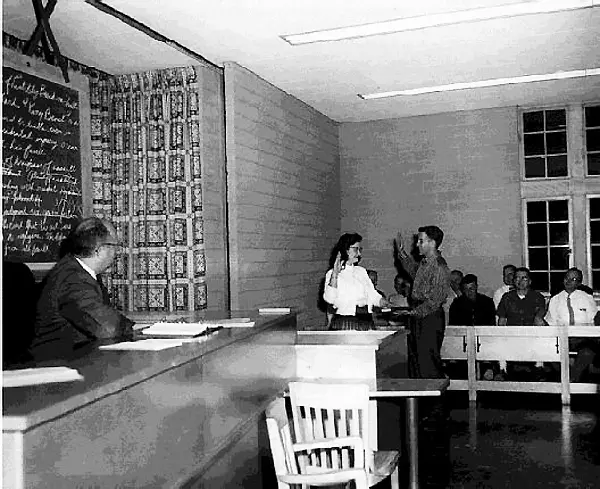

Members of the tennis team receive awards from President Philip Nash, ca. 1941.

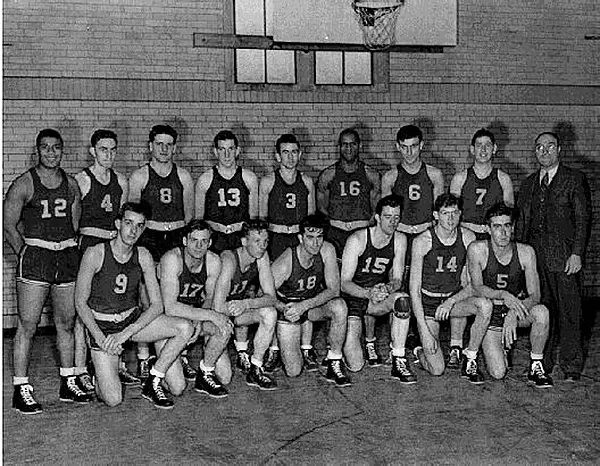

The basketball team of 1941-42, coached by Harold "Andy" Anderson, played in the National Invitational Tournament in Madison Square Garden . The teams of 1939 and 1943 also played in the tournament.

Before the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, student sentiment at UT, as at most other college campuses, was firmly against U.S. involvement in the war. On April 20, 1939, the students rallied for University Peace Day, an annual event. UT President Philip Nash spoke to the students about the threat on the horizon. Although Hitler was months away from invading Poland and France, Nash believed war was inevitable, telling students that “even after spending much of my life resisting war, I nevertheless believe that war would be better than the surrender of freedom by democracies.” Anti-war sentiments evaporated quickly after Pearl Harbor.

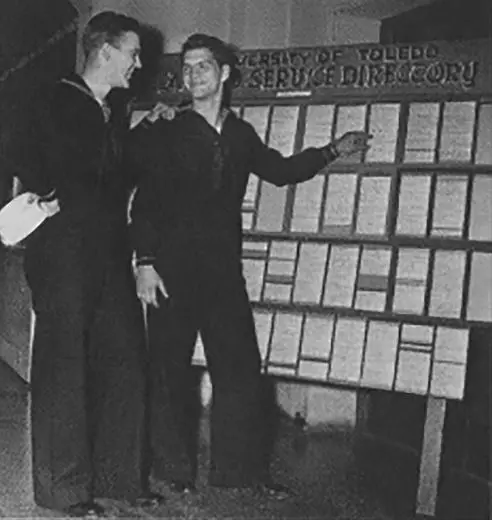

UT students Lyle Clark and Dodd Tonjes check information on the location of friends and classmates who are serving in the war at the Armed Services Directory, 1944.

Almost immediately, the impact of the war was felt on campus. Enrollments plummeted as men dropped out to enlist. In the first years, enrollment in the College of Engineering dropped 90 percent, and the College of Arts and Sciences lost 50 percent of its students. Many faculty accepted positions in the government and military. While the Selective Service Act gave students a one-year deferment, many declined it.

After war was declared, the government asked President Nash to identify facilities that could be used for the war effort, and he was authorized by the Board of Directors to make all available. One of the first programs instituted at the urging of the government was an accelerated degree program. When the draft age was lowered to 18 in 1942, UT instituted Saturday and summer session classes for high school students that allowed them to enter the university at the end of their junior year.

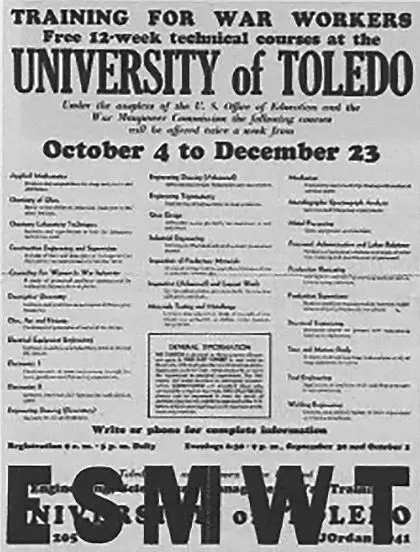

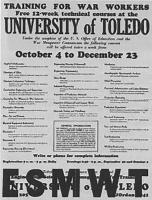

A poster advertising Engineering, Science, and Management War Training courses at UT, ca . 1943

The university and the government cooperated in many other programs. In April 1942, the U.S. Office of Education designated UT’s library as one of six key war information centers in Ohio. The library served as a repository for pamphlets and brochures that citizens could access to learn about the war effort.

The military quickly began contracting with colleges to provide training facilities because it was cheaper than building new ones, and universities were already organized to educate large numbers of students. UT offered war training programs for both military and civilian persons.

For civilians, UT was one of 200 colleges to offer Engineering, Science, and Management War Training (ESMWT) program classes. This program filled the need for engineers, chemists, and production supervisors for war-related industries and was especially suited for a university like UT, which already had an established engineering college. The free courses emphasized practical training over theory. At UT, ESMWT was administered by Delos Palmer, dean of the College of Engineering, and attracted over 1000 students in the first semester. Women especially were encouraged to take ESMWT classes. The program’s 1941 newsletter declared: “To Win the War, Women Must Work.” When the ESMWT program ended in 1945, some 15,000 Toledoans had been trained.

The Civilian Pilot Training Service was another federally-funded program offered at UT. Most of the trainees entered the service after graduation. The program offered ground training at the university and flight training at Toledo Municipal Airport. Over 100 men graduated from the program.

The success of civilian pilot training led the Army to expand it to enlistees in the Air Crew. Due to a lack of facilities at the Miami Beach base of the 27th College Air Corps Training Unit, the government contracted with UT to house, feed, and train a detachment of the division. Men from the Air Crew began arriving in March 1943 for academic, military, physical, and flight training. They lived in the Field House, and within 13 months almost 1,800 went through the program.

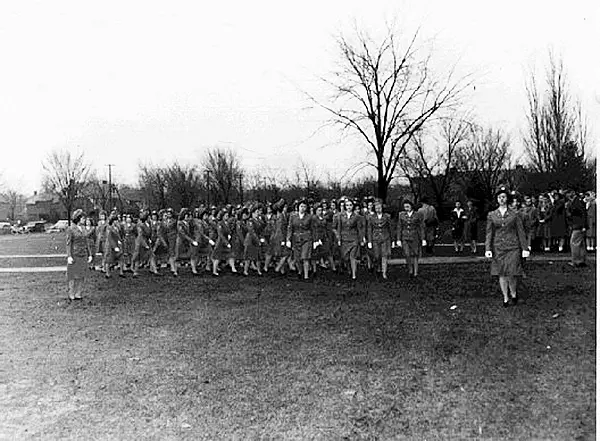

Another federal program trained women to become nurses in Army field hospitals. The university provided academic training, and five Toledo hospitals provided clinical practice. UT faculty supervised weekly military drills for the nurses. More than 300 graduated from the U.S. Cadet Nurse Corps program.

Women enrolled in the U.S. Cadet Nurses Corp program practice drills, 1944.

The war also provided federal money for research to universities. Under the Office of Scientific Research and Development, the federal government allocated $19 million throughout the country for university research. Because of the benefits of government-sponsored research for both universities and the government, such funding continued after the war, and led UT to organize the Research Foundation in 1945.

The wives of UT faculty members collect items for the Red Cross for the war effort, ca. 1942

Student social life also changed with the war. War Chest fund drives raised money for groups such as the USO and the War Prisoners’ Service. UT was the first university in the country to have a Red Cross chapter, and the group sponsored knitting bees to make sweaters for soldiers. Weekly air raid drills were held. With a dwindling number of male students, women assumed leadership roles on campus, serving as president of Student Council in 1944 and editors of the newspaper and yearbook from 1943 to 1945. Intercollegiate basketball and football were suspended in 1943, and did not resume until after the war.

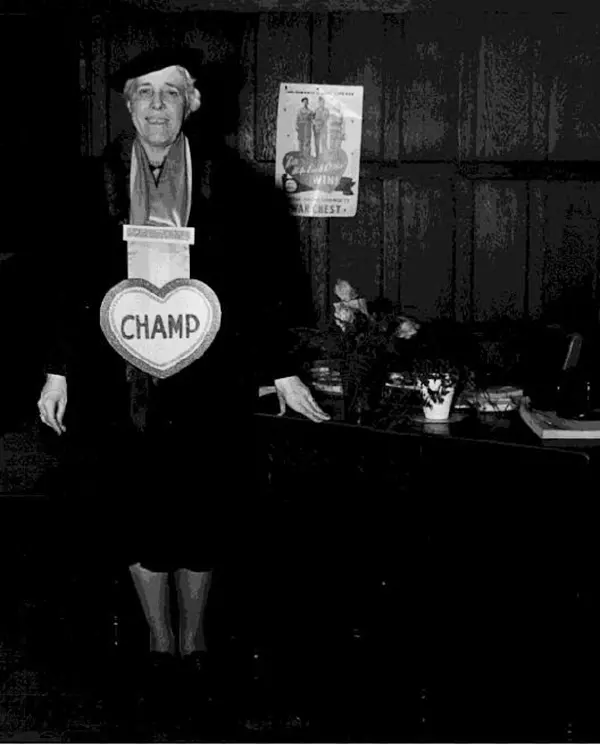

Lucille Mack, secretary to President Nash, displays the award she received as top fund-raiser for the Greater Toledo War Chest, 1944.

The full impact of the war on the University of Toledo, however, cannot be explained by knitting bees, federal programs, or enrollment declines. The real impact of the war was personal: disrupted lives, feelings of fear and anxiety, and more than occasionally, death. Over 100 UT students were killed in the war.

Members of Kappa Alpha Psi fraternity, 1943.

The war was also personal for President Nash. From 1929 to 1933, as executive director of the League of Nations Association, Dr. Nash had fought to end future wars by advocating that the U.S. enter the League. But in 1920, Congress voted against the League. As President Nash told the graduating class of 1939, “One of the greatest human catastrophes is war, and for twenty years I have been fighting against it. But we in this country, and the people of the world as a whole, appear not to have learned that the lesson that the only cure for anarchy is organization and the only cure for war is law.”

UT established a War Memorial Scholarship Fund in 1946 to provide money for the children of slain or missing UT students so that these children might someday attend the university. A plaque with the names of the war dead was placed at the entrance to the new library building (later named Gillham Hall) in 1953. It remains today as one of the lasting reminders of the impact of the war on the university.

The 1944 Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, more commonly known as the GI Bill of Rights, was both a way to reward veterans for their service in the war and a way to cushion the economic blow as they returned seeking peace-time jobs. The act paid veterans up to $500 for college tuition and provided a living allowance between $65 and $90 per month. Over 3000 veterans took advantage of the program at UT. Because most veterans were older and many had wives and children, some arrangements were required to house them. In 1945 the university purchased surplus military housing and moved it to campus to house the students. The area was dubbed “Nashville” by the students after President Philip Nash. Other surplus barracks were purchased from Camp Perry and erected behind University Hall as classrooms and laboratories.

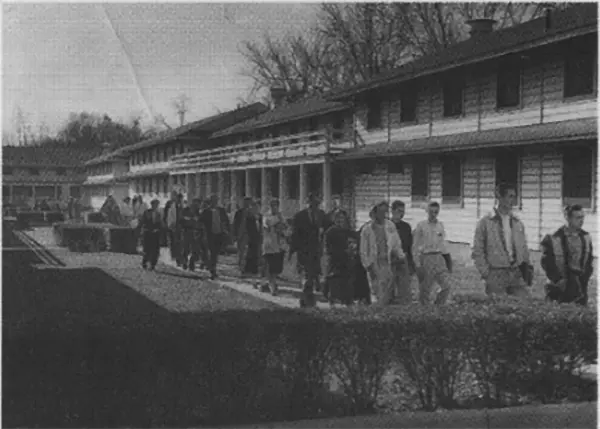

After the war, Army barracks from Camp Perry were constructed between University Hall and the Field House and served as classrooms and laboratories until the mid-1970s.

Following the war, veterans attending college on the GI Bill rented on-campus housing for their families in "Nashville" dubbed by students after President Philip Nash

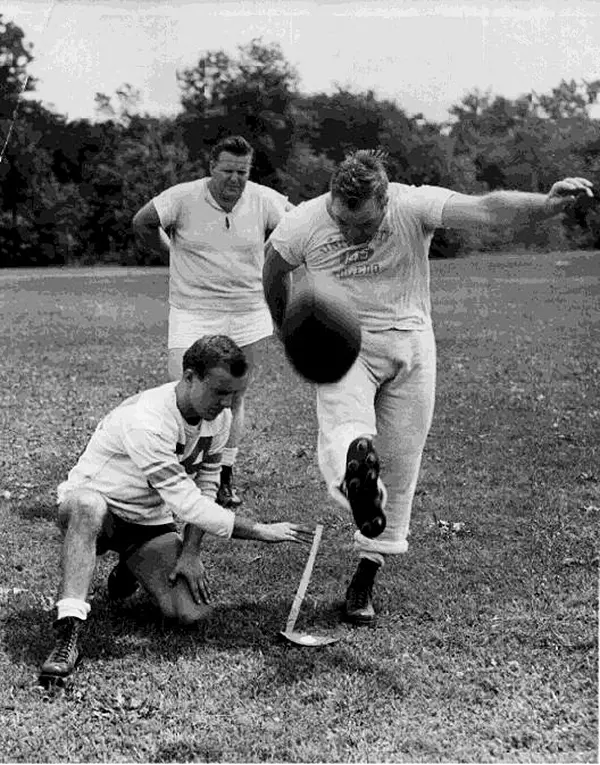

Football, which was suspended during the war, resumed in 1946.

Sports resumed at war’s end. Basketball returned in 1945 and football in 1946. Wayne Kohn, an employee of the glass manufacturer Libbey-Owens-Ford, suggested renovating the stadium by incorporating several glass additions and re-naming it the Glass Bowl. The first Glass Bowl game was held in 1946. Lights were also added that year, even though the first night game had to be moved due to an electrical short. In 1947, UT resumed athletic play with Bowling Green State University which it had canceled in 1936 after fan rowdiness and disagreements, and in 1949 UT joined the Mid-American Conference.

The first Glass Bowl banquet held at the Commodore Perry Hotel, 1946. Athletic Director David Connelly displays a lobster given him by the governor of Maine to mark the tournament game between UT and Bates College.

Blockhouse editor Richard Villwock receives help from yearbook advisor Jesse R. Long, 1947.

In many ways, the final casualty of the war for the University of Toledo was Dr. Philip Nash. In 1946 he became gravely ill with a heart condition, and he died in May the following year. Dr. Nash’s presidency had seen the university through the Depression and the war, a growth in the student population from 2000 students to over 6000, and a doubling of the budget to $500,000.

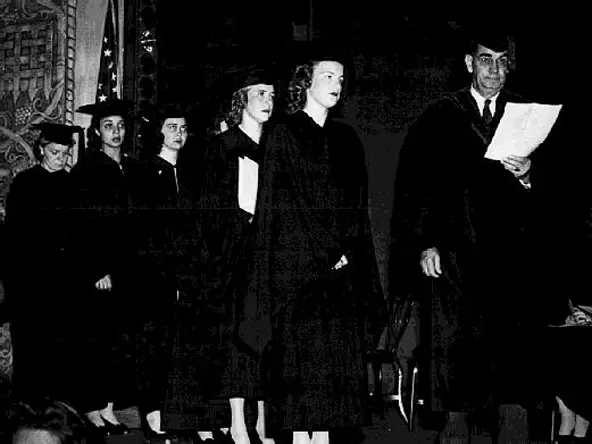

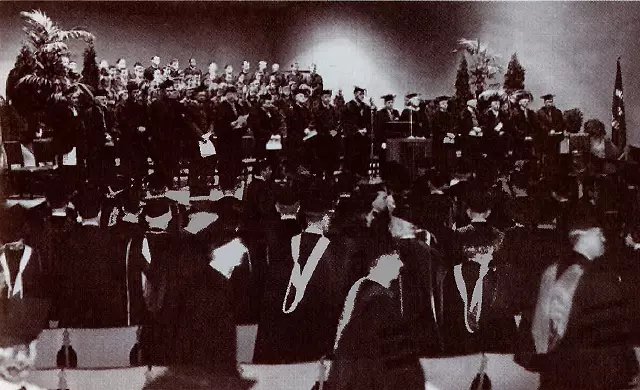

Left: Business students study for exams, 1946. Right: Leading a commencement ceremony in Doermann Theater is Raymond L. Carter,

who served as Dean of Administration from 1934-1951 and Acting President from 1947-1948.

The inauguration ceremony of President Wilbur W. White , 1948.

In 1947, the Board selected Wilbur W. White to replace Dr. Nash. President White, who had come to the post from Western Reserve University, was inaugurated in a ceremony at the Peristyle at the Toledo Museum of Art. He proposed a progressive ten-year development plan calling for new buildings, including a home for the College of Engineering and a combined law school and library building. President White did not live to see many of his plans come to fruition as he died in November 1950. He was succeeded temporarily by a three-member Interim Operating Committee consisting of John Brandeberry, Jesse Long, and John Turin.

The Interim Operating Committee governed the university during the period between the death of Wilbur White and the assumption of the presidency by Asa Knowles in 1951. The committee consisted of John J. Turin, John B. Brandeberry, and Jesse R. Long.

The period of administrative turmoil that began with Dr. Nash’s death in 1947 ended in 1951 with the appointment of Asa S. Knowles as president. Dr. Knowles had been a vice president at Cornell University before coming to UT and had a background in administration. He saw to the completion of a new men’s dormitory in 1952 and the new library in 1953. He expanded educational programming for adult students and created the Greater Toledo Television Foundation as a way to utilize television for educational purposes. WGTE Channel 30 was licensed by the Federal Communications Commission and began broadcasting in 1958.

A student readies for commencement, ca. 1950

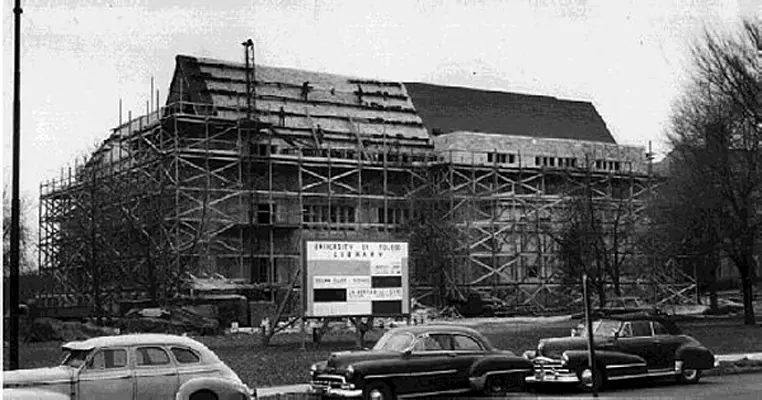

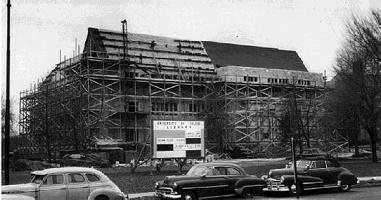

A new library and law school building under construction in 1952.

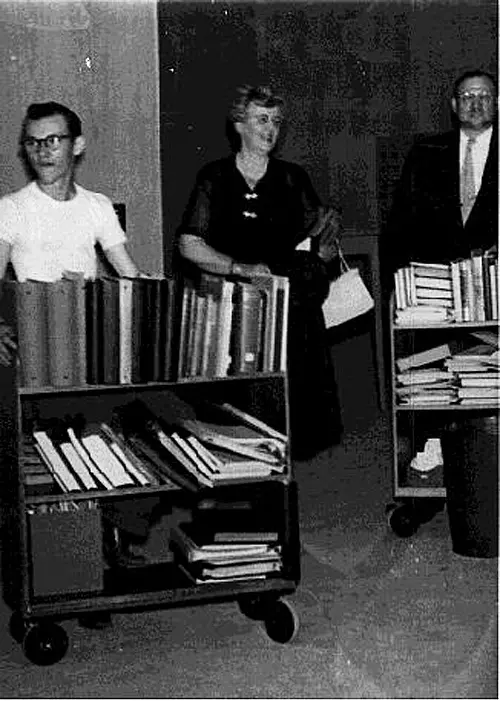

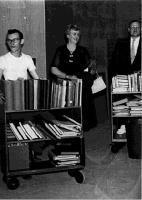

Librarian Mary Gillham supervised moving the library's holdings to the new building, 1953

One unfortunate incident that brought UT national publicity during Dr. Knowles’s tenure was a game fixing scandal involving UT basketball players. The 1950 team was an exceptional team with a streak of wins. Suddenly, the team began to have problems. After a game against Niagara University, three players were charged by a New York district attorney with shaving points at the request of a gambler in exchange for $500 payments. One more player was later charged with doing the same at earlier games. The players were allowed to withdraw from the school. A new law passed by the Ohio legislature after the scandal made game fixing by any amateur athletes subject to fine and imprisonment.

Law students practice their skills in Moot Court.

Students socialize in the Student Union in Libbey Hall, ca. 1950.

Students in the post-war period seemed to lack much interest in political affairs, and were conservative in dress and attitude. Some dubbed these students the “Silent Generation.” Even the outbreak of the Korean War did little to disrupt the climate. The most prevalent counter-culture expression of revolt was the “panty raid.” This activity was given a unique twist in 1953 at the University of Toledo when women raided a male dorm in retaliation for a raid on their dorm.

Several members of the cheerleading squad of 1957-58: Tam Townsend, Pat Rankin, Mikki Eppard, and Kathy King.

In 1956, Toledo attempted to pass a city charter amendment that would have provided a 2-mill levy for capital improvements, including new buildings for UT. The levy was soundly defeated. The city informed the university that it could afford only half of the estimated cost of the proposed engineering building, and the rest would have to come from private sources. Over $1 million was raised, with the biggest contribution from Charles A. Dana, head of the Dana Corporation.

Arts and Sciences dean Andrew J. Townsend (left) presented gifts to President Asa S. Knowles at a party marking the departure of Dr. Knowles from UT in 1958.

Asa Knowles resigned the presidency in 1958 to become president of Northeastern University. His last official act was to meet with City Council to discuss the future financing of the university. Over 12 percent of the city’s budget was allocated to the university, and clearly this could not continue. The Council suggested that further study be given to acquiring financial assistance from the state, which would relieve the city of the burden of financing it while providing the funding needed for the university to grow.

The UT Chorus appeared on the Ed Sullivan Show in 1958.

Chapter 4. A Period of Change, 1960s-1980s

President William S. Carlson served as president from 1958-1972.

In January 1959, a special committee of Toledo City Council met with the University of Toledo’s new president, William S. Carlson, to discuss the future funding of the university. The university’s allocation was taking more and more of the city’s meager budget, and students were also being asked to pay a larger share. Toledo residents had two particular gripes. In addition to funding the municipal university with their tax dollars, they had to pay state taxes to support the state universities. They were also supporting students living outside the city limits who attended UT.

While many in City Council wanted to see the university turned over to the state, the university’s Board of Directors preferred state financial assistance and retaining UT’s independence. Three bills introduced into the state legislature in 1959 proposed a per-student subsidy for the state’s three largest municipal universities: Akron, Cincinnati, and Toledo. The bills stalled in the face of opposition from presidents of the state institutions who felt any funding for the municipal universities would come from their pockets.

The financial crisis worsened. Tuition was increased again and salaries frozen. City Council agreed to place a 2-mill levy on the ballot on October 6, 1959, to raise $1.7 million a year for the university. UT launched a vigorous campaign in support of the levy, and it passed by just 144 votes.

The new Student Union under construction. The building was completed in 1959.

The UT Dancing Rockettes, the first collegiate dance team in the country, was organized by Sports Information Director Max Gerber in 1961 and modeled after the group by the same name that performed in Radio City Music Hall.

With finances settled for a time, Dr. Carlson turned his attention to improving the academic standards of the university. He added research and scholarship to the job requirements of the faculty. In 1962 an honors program was instituted, and the first Ph.D. was awarded that year. The university bought several new parcels of land, adding access from Secor Road and space for a new men’s dormitory. The National Defense Education Act, passed in 1958, granted colleges $9 from the federal government for every dollar raised locally for scholarships. To help in fundraising, the Alumni Association created the non-profit University of Toledo Alumni Foundation. A new home for the president was acquired as a gift, and another gift of $1.4 million from the estate of Walter and Grace Snyder was used for a new building for the College of Education.

The Engineering-Science building was constructed with city and private funds in 1960.

Student socialize in the dormitory cafeteria, 1961 (left); An annual fundraising event was the Alumni Foundation's Phonathon, which started in 1962 (middle); Students stand in line in the Field House to register for classes in 1963 (right)

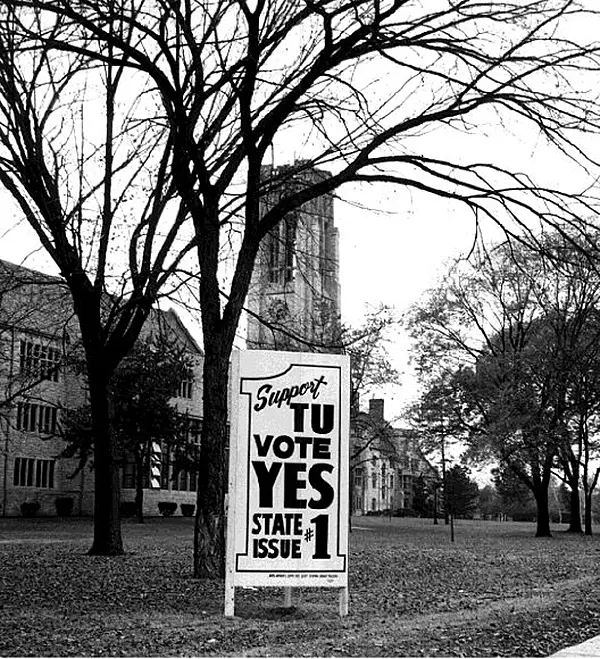

In 1963, UT urged voters to approve State Issue 1, which raised $250 million in capital improvement money for building projects at institutions of higher education (left); Freshmen students board busses for Freshman Camp, 1963 (middle); Mrs . Arthur Zepf, vice chair of the UT Board of Directors, places a time capsule in the cornerstone at the dedication of Snyder Memorial, April 22, 1964 (right).

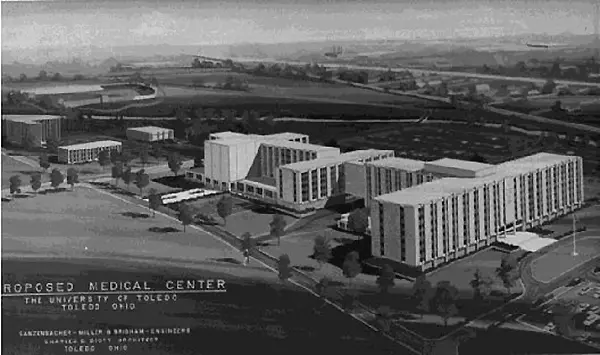

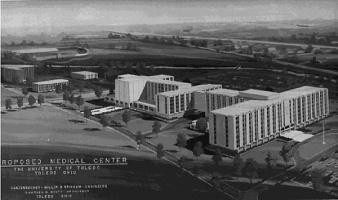

Not all of President Carlson’s plans succeeded, however. The city’s mayor, Michael Damas, began a campaign in 1961 to land a new state medical college in Toledo. A consultant’s report suggested that the institution should be built in association with, and on the campus of, the University of Toledo. But this plan was dealt a blow when former Toledoan Michael DiSalle lost his re-election bid for governor to James Rhodes. Rhodes abolished the commission responsible for higher education planning (which had viewed Toledo’s plan favorably) and created a new agency, the Ohio Board of Regents. Several critical miscommunications with the state and pressure from The Blade and its publisher, Paul Block, Jr., led the trustees of the medical college to select the site of the former state hospital for the institution rather than a site on the UT campus. Furthermore, the Medical College of Ohio at Toledo was established as an independent state university.

Plans for the proposed medical center for The University of Toledo, 1964. The buildings were never constructed. Instead, the Medical College of Ohio at Toledo was created as an independent state university on the grounds of the old state hospital on Arlington Avenue.

Another unsuccessful effort by Dr. Carlson concerned building a new home for the University Community and Technical College on the site of the Rossford Ordnance Depot. The depot was to be deactivated, and in 1962 Congressman Thomas Ludlow Ashley tried to negotiate a deal to sell the site to UT for the community college. The deal was blocked, however, by residents owning adjoining land parcels who opposed it. With this site unavailable, Dr. Carlson suggested building the new campus on Jesup Scott’s original land donation of 1872 at Nebraska and Parkside. The Toledo newspaper opposed the move because it was uncertain if this land was owned by the university or the city. The university took the matter of ownership to court and received clear title. With the help of additional tax money, construction began on a new Community and Technical College campus in 1967.

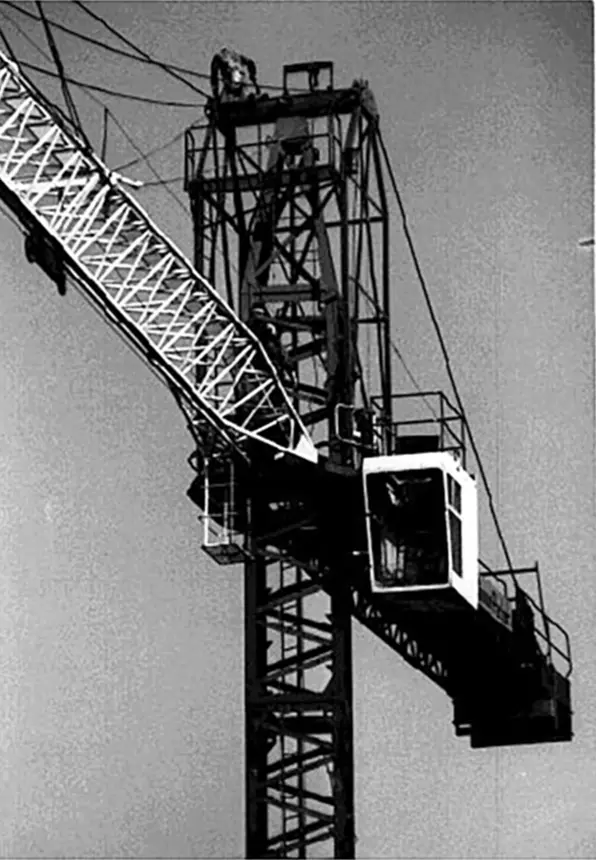

Construction progresses on buildings at the Community and Technical College campus located at Scott Park, 1969 [*]

The ACT group, as the three municipal universities of Akron, Cincinnati, and Toledo were known, continued to press the state for financial assistance. Governor Rhodes agreed in 1965 to provide a state subsidy of $200 per student (despite opposition by the state universities). This was the beginning of state assistance for the University of Toledo.

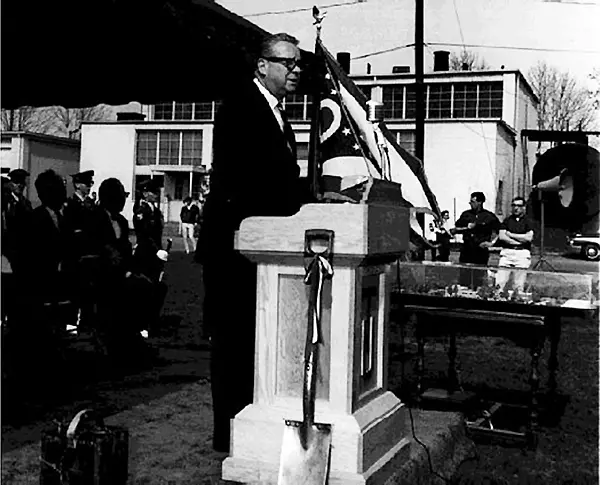

Ohio Governor James Rhodes spoke at the groundbreaking ceremony for a new chemistry and biology building (later Bowman-Oddy Laboratories), 1965.

On July 3 of that year, the Ohio General Assembly passed a bill providing for the most fundamental change in the university’s history. The bill incorporated the University of Toledo into the state’s system of higher education. UT’s Board of Directors unanimously endorsed the bill.

Women play basketball in the Field House women's gym, ca. 1965.

President Carlson confers with Ohio Governor James Rhodes before the ceremony marking the transition of The University of Toledo from a municipal institution to a state institution, 1967

Effective July 1, 1967, the University of Toledo became a state university. State funding relieved the city of the burden of supporting a growing university, and provided capital improvement funds for new buildings. On the day of the ceremony marking transfer of ownership, groundbreaking was held for the Health Education Center and an addition to the Engineering-Science Building. Ritter Planetarium and Observatory (1968), the Law Center (1972), and a new library (1973) were soon to follow. Two other proposed building projects never happened, however. A music hall and auditorium between University Hall and the Student Union was rejected because its architecture was too modern. A proposal to put a dome over the Glass Bowl to allow its use for both basketball and football was rejected because of criticism from The Blade and from the students. The Blade and its publisher wanted the university to build a new sports facility downtown as part of the city’s revitalization efforts. The students did not want to pay additional fees to cover the Glass Bowl’s renovation, estimated at $8.5 million. The plan was dropped, and the stadium’s renovation was delayed until 1990.

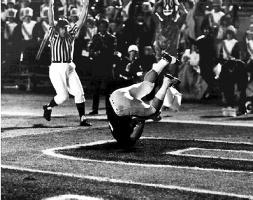

The construction of Ritter Planetarium and Observatory, 1967 (left); Fans of the football team travel to Florida by bus to see the team play in the Tangerine Bowl in 1969 (middle); Dick Seymour scores a touchdown in the Tangerine Bowl of 1969. Between 1969 and 1972, the UT football team scored 35 consecutive victories, the second longest winning streak in modem major collegiate football history (right)

Becoming a state university also produced administrative changes. The governing board, now called trustees, was appointed by the governor. To help administer the expanding institution, Dr. Carlson appointed a new group of vice presidents. And in 1968, the university was required to change from semesters to quarters in order to conform to the calendars of the other state universities.

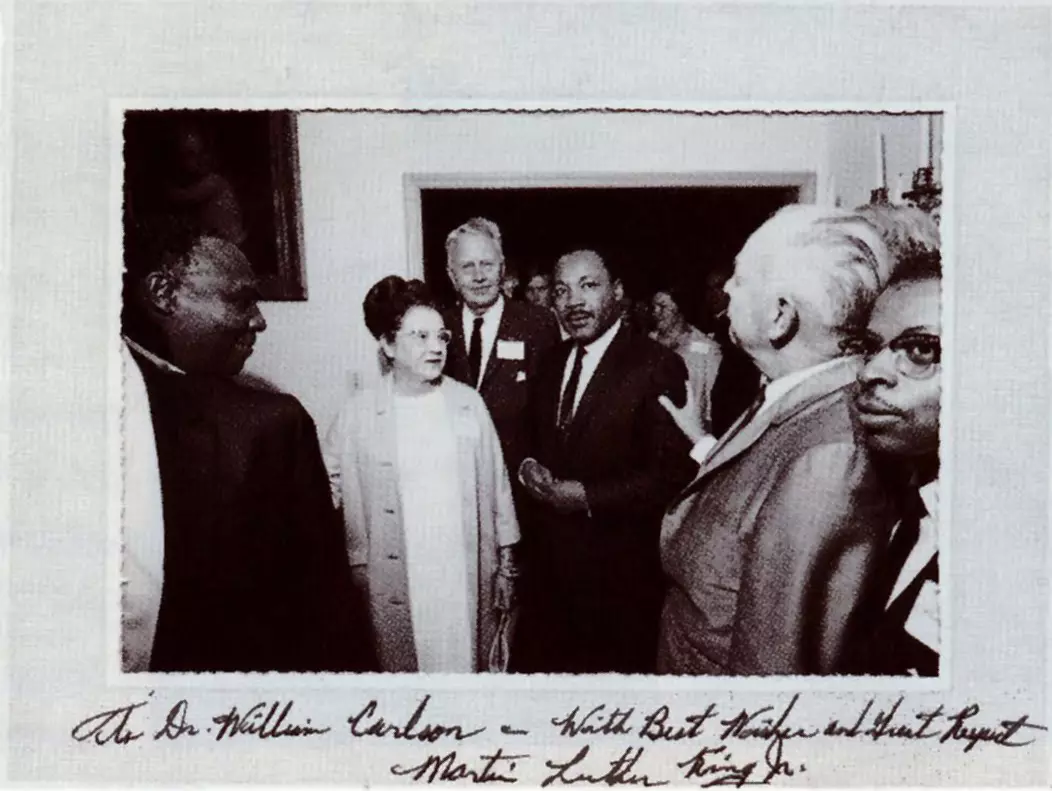

President William S. Carlson met civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. at a reception in Toledo, 1967.

Inspired by the election of President John F. Kennedy, college students in the 1960s awakened from the “Silent Generation” of political apathy. The Civil Rights movement led many to protest segregation and volunteer as “Freedom Riders.” But it was the Free Speech Movement that began at Berkeley, California, in 1964 that influenced a decade of student protests, including many at the University of Toledo.

Republican Presidential candidate Barry Goldwater tried to address the students in the Field House in 1964, but was drowned out by supporters of opponent Lyndon Johnson.

UT officials were embarrassed in October 1964 when Republican presidential candidate Barry Goldwater tried to speak at the Field House and was drowned out by supporters of Democrat Lyndon Johnson. The event received national press coverage. On May 5, 1966, local members of the Students for a Democratic Society protested the military draft outside Dana Auditorium where male students were testing to qualify for draft deferments. A few days later, SDS members disrupted a ROTC Honors Day review. To avoid more protests, a committee of faculty and students produced the Joint Statement of Rights and Freedoms of Students as the basic policy governing student privileges. After the policy was approved by the Board of Trustees, students were given representation on committees that allocated student funds.

Students relax after class in a traditional way, ca. 1967.

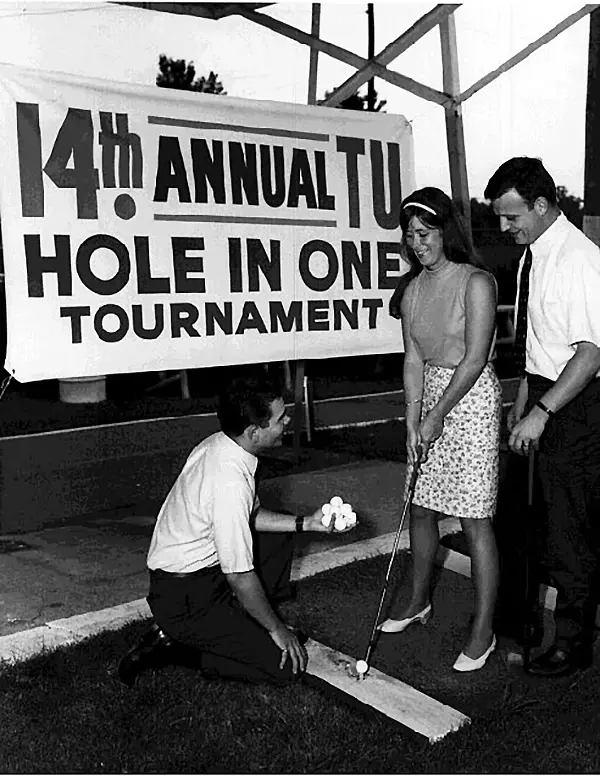

The Alumni Association's popular Hole in One Tournament helped to raise thousands of dollars for UT scholarships. This is a photograph of the 1968 event.

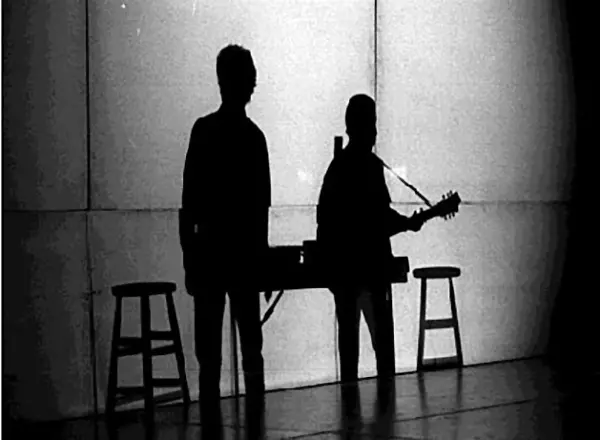

Simon and Garfunkel appearing in concert in the Field House, 1968. (Photo by Bill Hartough.)

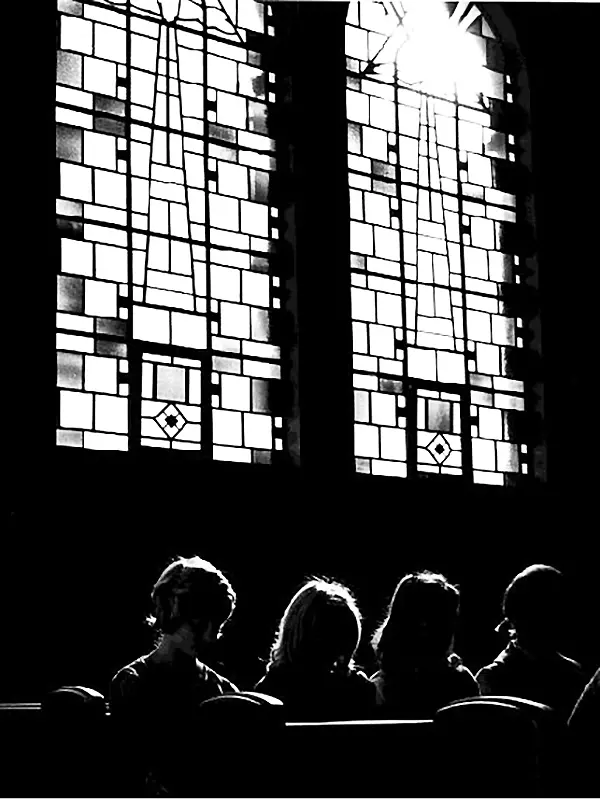

The protests by UT students were peaceful compared to other universities. Theater students waged a sit-in in May 1967 to protest the allocation of space in Doermann Theater to the Student Records Office. In April 1968, dormitory students started a “food riot” over the quality of food served to them. Students opposed to the war in Vietnam again disrupted the ROTC Awards Day ceremony on May 7, 1969, and this time four were arrested. The following week a group confronted President Carlson and demanded that ROTC be abolished on campus, and several students stormed his office a few days later. One student was arrested for this action. On October 15, 1969, over a thousand UT students and faculty participated in the national Vietnam moratorium by marching from campus to Gesu Church for memorial services for the war dead.

Some of over 1000 UT students who participated in the national Vietnam War moratorium observance, October 15, 1969. (Photo by Bill Hartough.)

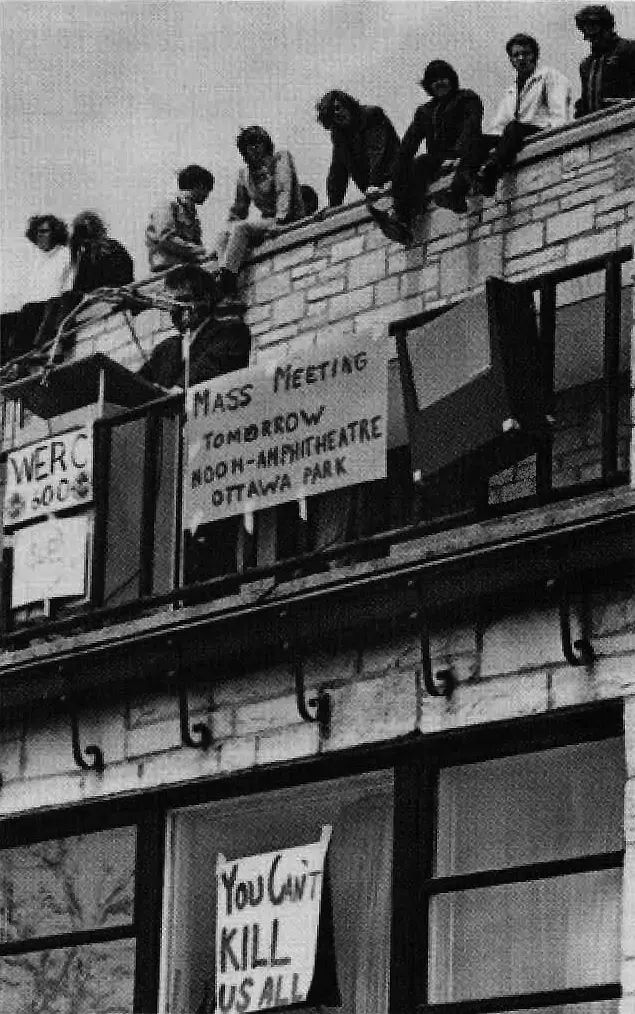

Student protests reached a crisis stage on May 4, 1970, when members of the Ohio National Guard killed four students protesting the Vietnam War at Kent State University. That afternoon, the UT Student Senate met and requested a moratorium on classes as a memorial to the slain students and to provide time for students to hold workshops to discuss the event. The next afternoon, newspaper columnist Carl Rowan, who had been scheduled to speak as part of the University Convocations series, spoke outside at a large rally, where he was joined by several student leaders and Dr. Carlson. The Faculty Senate passed a resolution deploring the violence at Kent State and asked that the moratorium be continued for the rest of the week. The week ended with a candlelight procession, and the campus remained peaceful.

One of the UT student rallies held fallowing the events at Kent State, 1970.

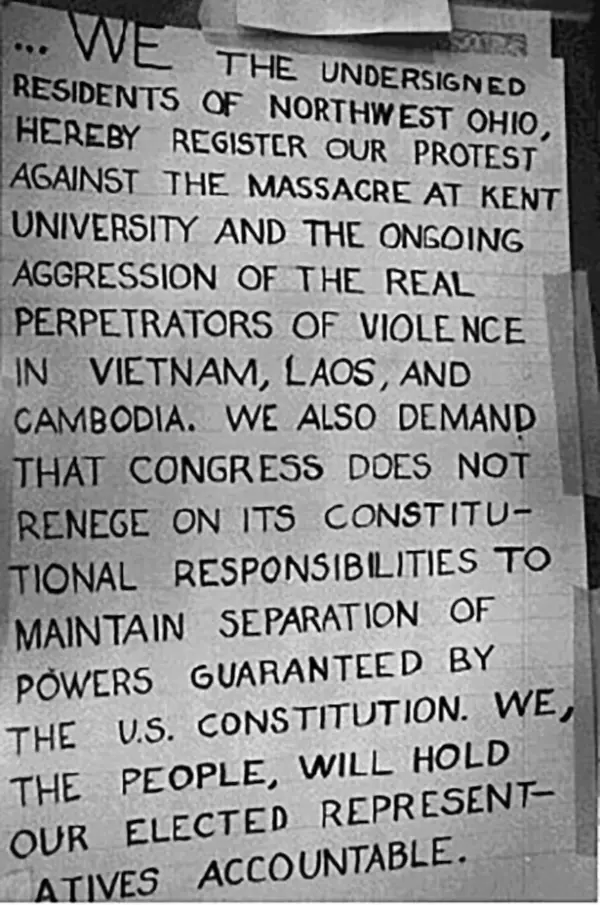

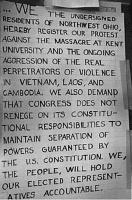

A petition signed by thousands of UT students expressed outrage at the violence at Kent State University and the Vietnam War, 1970

However, tensions rose again on May 15 when a shooting at Jackson State University in Mississippi killed two black students. To protest what the students felt was a lack of sympathy by Dr. Carlson for the death of these students, black students blocked the entrance to University Hall on Monday, May 18. President Carlson met with a group of these students, and agreed to hire more black faculty and graduate assistants and start a Black Studies program.

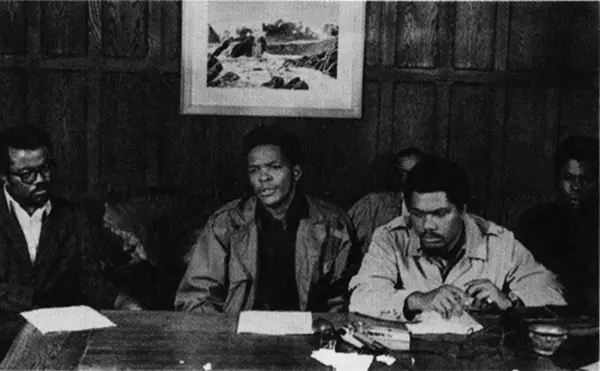

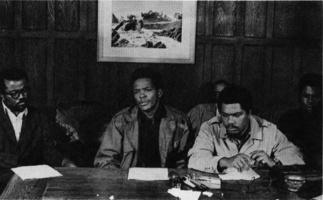

Black student leaders met in President Carlson's office following the death of two students at Jackson State University in Mississippi. Talks between the students and Dr. Carlson ended a blockade of University Hall, May 18, 1970.

The events of the first few weeks in May 1970 ended peacefully with a student referendum on May 20-21. An overwhelming majority favored returning to normal business. They also asked that the Army Reserve be removed from campus (but favored ROTC remaining), and asked that a letter be sent to President Richard Nixon stating their views on the war in Vietnam.

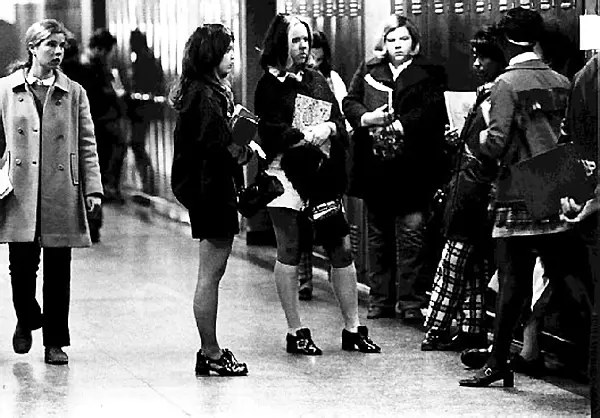

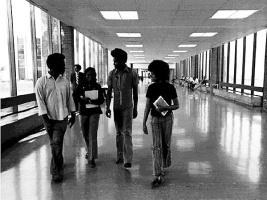

Students at the Community and Technical College, ca. 1970.

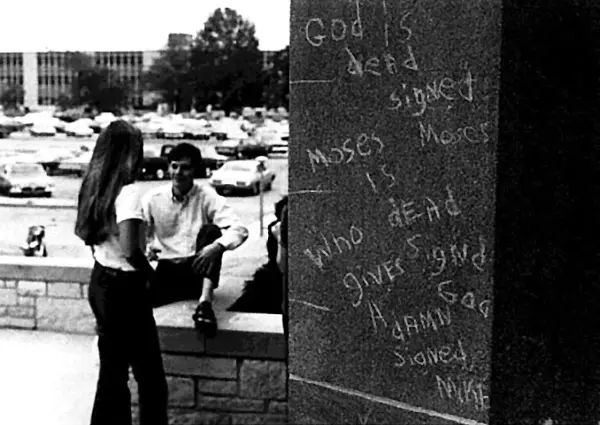

UT students, like those at many universities at the end of a violent decade, expressed cynicism about political events. This photograph was taken in 1971. (Photo by Bill Hartough)

Immediately after the Kent State shooting, Governor James Rhodes set up a series of committees to study the issue of campus unrest in Ohio. Among the outcomes of this commission was the request for a code of conduct for students and faculty at state universities and improvements in campus security.

Progress is made on both William S. Carlson Library and the addition to the Student Union, 1971.

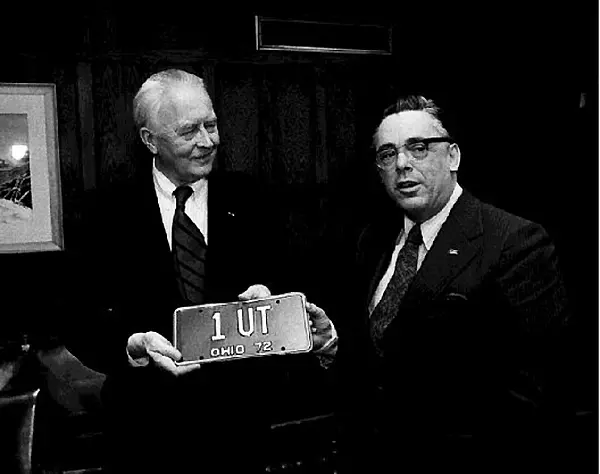

UT marked its centennial in 1972 with a year of celebrations. Ohio license plates were issued in blue and gold to commemorate the event. Plans were made for a major capital campaign called the Centennial Fund Drive to serve as a lasting legacy to the year. Dr. Carlson received an honorary degree at a formal convocation in the Field House. And The Tower Builders: The Centennial History of The University of Toledo, by Frank R. Hickerson, was published.

Mrs. Frank Hickerson is presented with a copy of The Tower Builders, a history of UT published as part of its centennial and written by her late husband, Jesse Long.

Dr. Carlson receives his blue and gold Ohio license plate commemorating UT's centennial from Donald Curry, 1972.

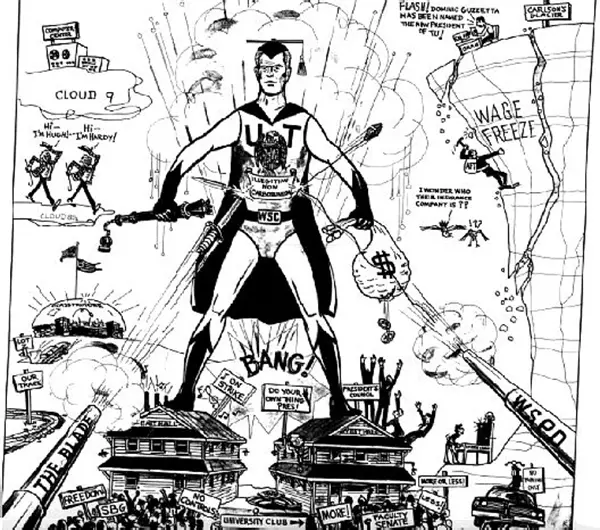

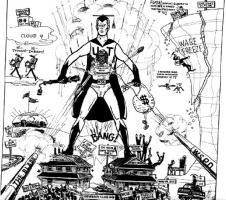

Dr. Carlson received this card on his birthday in 1971. The drawing, by Thomas Durnford, depicted many of the events that occurred during Dr. Carlson's tenure, and was inscribed with "Happy Birthday-Super President" on the back.

President Carlson announced his intention to retire in 1972. Dr. Glen R. Driscoll, chancellor of the University of Missouri-St. Louis, was selected as his successor. Dr. Driscoll oversaw further expansion of the university’s physical plant with the additions to the Student Union (1972) and the Law Center (1978), and several new buildings including the Center for Performing Arts (1976), Centennial Hall (1976), the Center for Continuing Education (1978), and Stranahan Hall (1984). When Dr. Driscoll retired in 1985, the continuing education building was named for him. Plans were also made for a new downtown complex of classrooms and meeting rooms, part of downtown Toledo’s revitalization efforts. Construction began on UT’s SeaGate Centre campus in 1985.

In 1972, William Carlson retired from the presidency of UT and was replaced by Dr. Glen R. Driscoll.

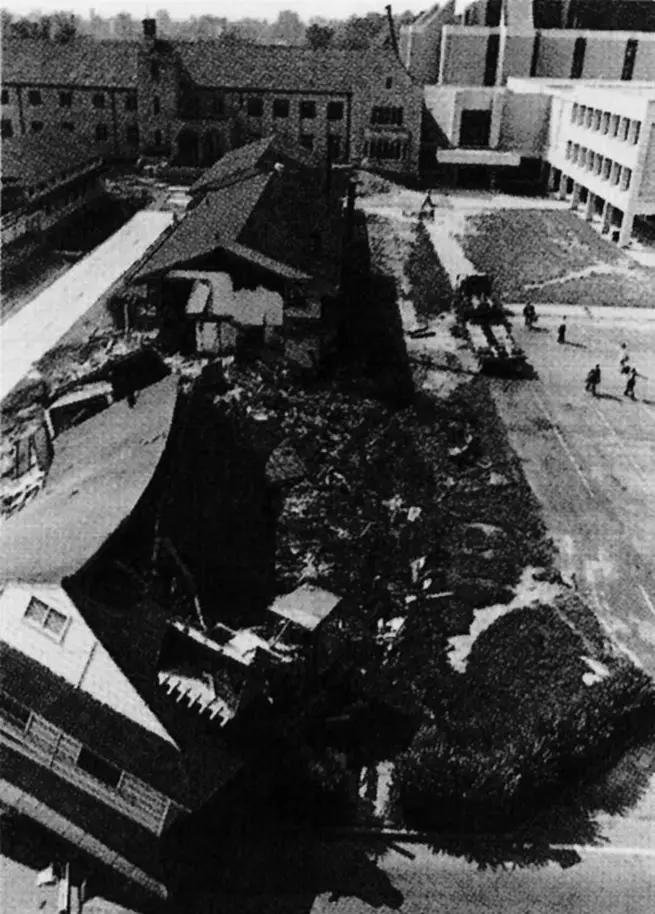

The late 1970s saw the university undertake its most important beautification project, Centennial Mall. Traffic was diverted from the middle of campus, and the parking lots and army barracks between University Hall and the Student Union were demolished. These eye-sores were replaced with a 9-acre landscaped mall which was dedicated as part of the Homecoming festivities in 1980. In 1981, the university celebrated 50 years of the Bancroft Street campus.

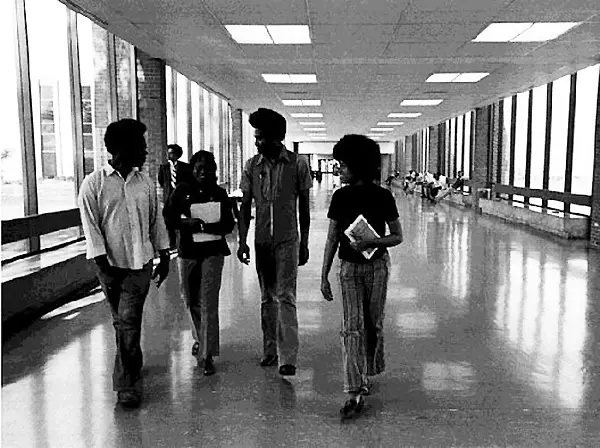

Scenes of student life, ca. 1972 (left); Movers help transfer the library's holdings into the new William S. Carlson Library building, 1973 (middle); Scenes of student life, ca. 1973.

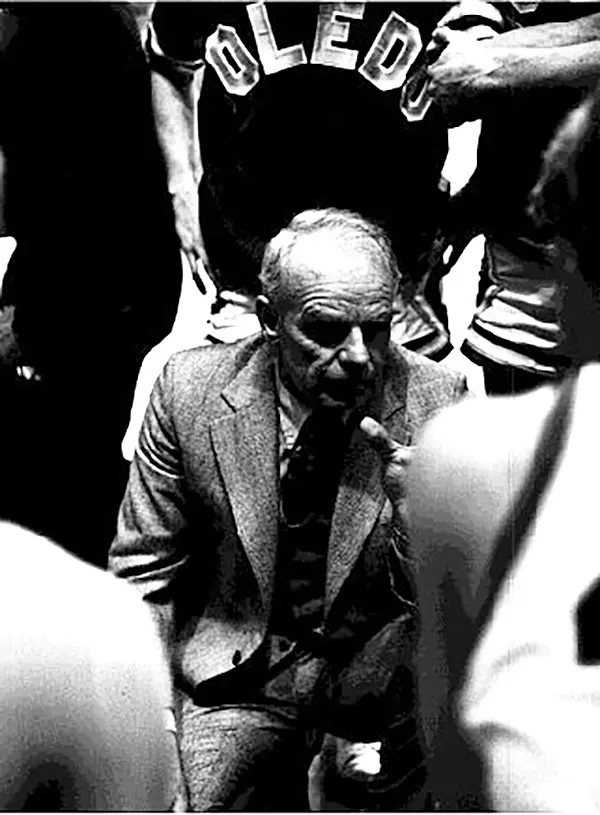

Rocket basketball greats Ralph Lewis ( 1960- 1962), Steve Mix ( 1967-1969), and Ray Wolford ( 1962-1964) help break ground for Centennial Hall, 1975 (left); Scenes of student life, ca. 1975 (middle); Bob Nichols, the most successful basketball coach in the history of the Mid-American Conference, who coached the UT team for 22 years beginning in 1965. He led the basketball team to conference championships in 1966-67, 1971-72, 1978-79, 1979-80, and 1980-81 (right)

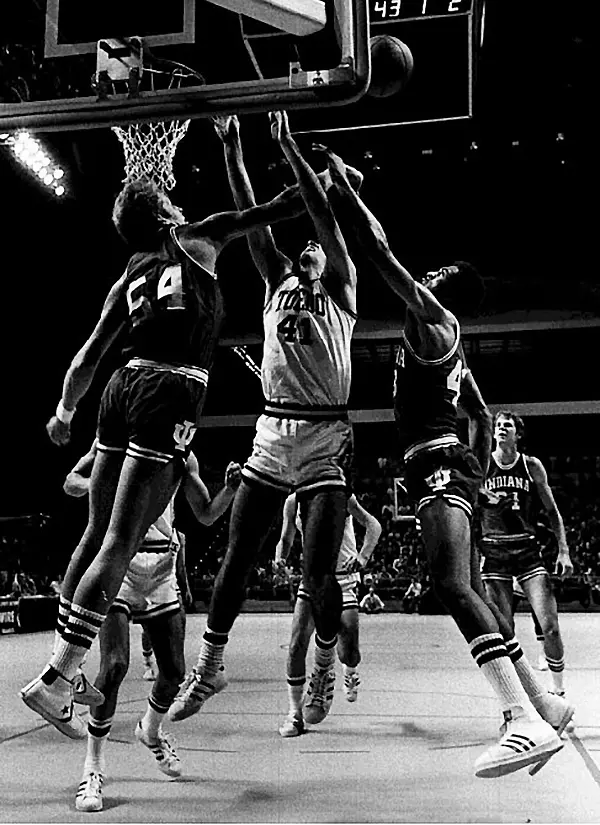

The inaugural game of Centennial Hall (now Savage Hall) in 1976 when UT beat the basketball powerhouse Indiana University by a score of 59 to 57, ending Indiana's 33-game winning streak (left); A Performance by Bob Hope marked the opening of Centennial Hall, 1976 (middle); In 1979, the parking lots and old Army barracks that occupied the center of campus were tom down to make room for Centennial Mall (right).

The 1980s were a time of record enrollment growth. Between 1979 and 1989, UT was the fastest growing state university in Ohio, with the student population increasing from 18,000 to over 24,000. These enrollment gains were made in spite of periodic economic recessions that hit northwest Ohio particularly hard.

The Catharine S. Eberly Center for Women was dedicated on Dec. 7, 1980, in honor of the late Board of Trustees member. President Glen Driscoll (left) and trustee Lois Kennedy (right).

Because UT was located in an urban setting, Dr. Driscoll sought to develop ways that the university could contribute to its surrounding community. He founded the Urban Affairs Center, the Management Center, and the Catharine S. Eberly Center for Women in an effort to serve the government, businesses, and needy populations of northwest Ohio. The community gave back to the university too with an increase in private giving which placed UT in the top 100 public universities in the nation for fundraising.

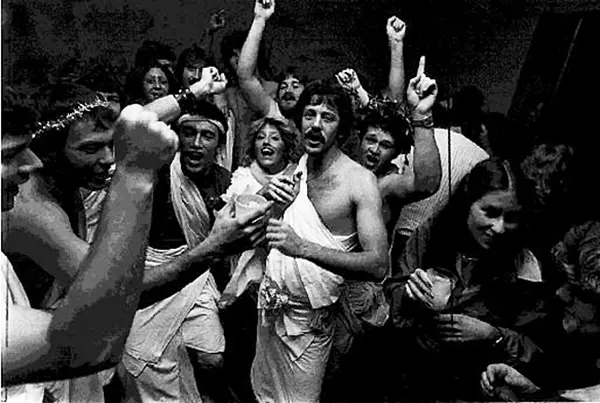

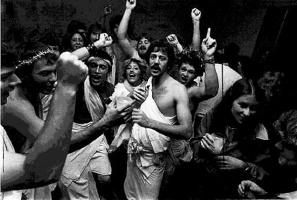

A fraternity "Toga" party, ca. 1980, popularized by the movie "Animal House."

In 1983, former Toledoan Jamie Farr received an honorary degree from UT.

In March 1984, Dr. Driscoll announced that he would retire the following spring. Dr. James D. McComas, president of Mississippi State University, was selected to replace Dr. Driscoll following a national search. He was formally inaugurated at a ceremony in October 1985.

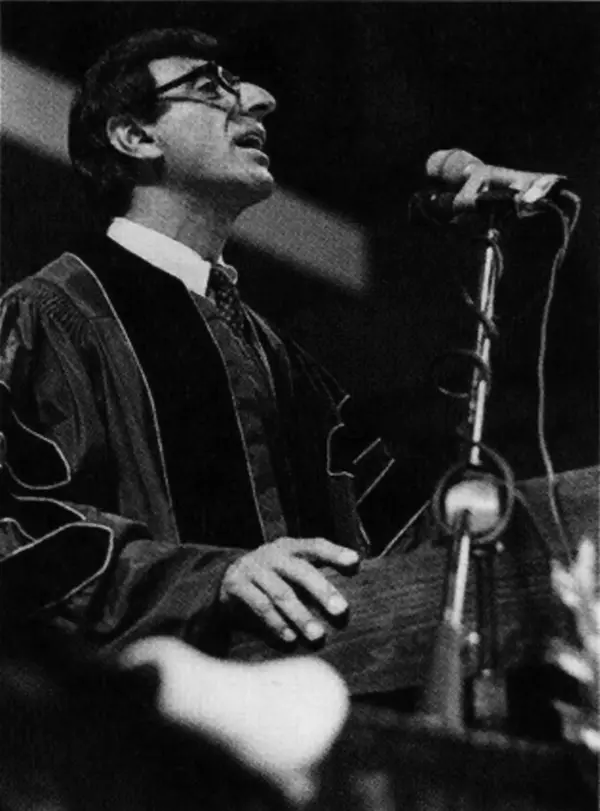

President James D. McComas and Ohio Governor Richard Celeste confer at President McComas's inauguration ceremony, 1985.

Dr. McComas continued the expansion of the university’s facilities. McMaster Hall (1987) was completed, and plans were made for the Student Recreation Center (1990), the Larimer Athletic Complex (1990), the Greek Village (1990), and renovations to the Glass Bowl Stadium (1990) during his tenure. The university purchased land from Owens-Illinois for a new building for the College of Engineering. A new master plan unveiled in March 1987 provided guidance for future campus development. Some of the building projects were controversial, however, especially among the faculty. The university sold bonds to cover the cost of many of the projects, and some faculty expressed concern about the burden of the debt on the future of the institution.

Work progresses on Stranahan Hall, 1984. (Photo by Bill Hartough.)

The university expanded its programming to a third campus located downtown at SeaGate Centre, 1987. (Photo by Liz Brandt.).

In addition to new buildings, Dr. McComas tried to improve relations between the university and the community by promoting UT in the press. To stress academic excellence, Dr. McComas established the Presidential Scholars program, and began efforts to attract more National Merit Scholars. His tenure at UT was brief, however, as he resigned in 1988 to become president of Virginia Polytechnic University. John Stoepler, dean of the College of Law, was named interim president while the search began for a replacement.

McMaster Hall was dedicated in 1987 as the new home for UT's Physics and Astronomy Department. The building was named for Helen and Harold McMaster, who donated the funds to help complete the project.

Chapter 5. The 1990s and Beyond

The inauguration ceremony for Dr. Frank E. Horton, April 13, 1989.

Dr. Frank E. Horton, president of the University of Oklahoma, was selected the University of Toledo’s thirteenth president in October 1988. His presidency would face many challenges. The phenomenal growth of UT that began in 1967 and continued apace for 20 years could not be sustained indefinitely. The 1990s brought declining enrollments, periodic economic recessions, financial struggles, and a leveling-off of state support.

The dedication ceremony for the fraternity and sorority housing complex (later named James D. McComas Village), 1990.

To meet the challenges of the 1990s, Dr. Horton began a lengthy strategic planning effort to chart a course of targeted, purposeful growth. A steering committee oversaw the work of ten special task forces. Each task force created a specific action plan. To help achieve the plan’s many goals, in 1993 the university launched a $40 million fundraising campaign called UT40.

As part of the renovation of the Glass Bowl Stadium, older sections of the seats are demolished to make room for the new, 1991.

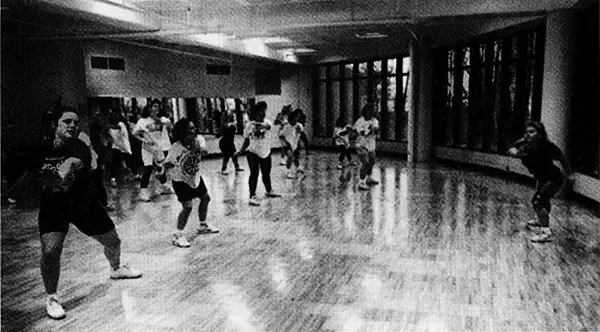

An aerobics class in the new Student Recreation Center, 1991 .

The university continued to expand its physical environs in the 1990s. A new Academic Center and Residence Hall (1992) was built to house a university-wide Honors Program. Other new buildings included the Student Medical Center (1992), the Center for the Visual Arts at the Toledo Museum of Art (1992), the International House Residence Hall (1995), and Nitschke Hall (1995). Another major expansion of the campus took place in 1990 when UT leased space that had housed a shopping center at Dorr Street and Secor Road. The Southwest Academic Center, as it was named, was purchased by UT in 1995 and will undergo additional renovation. And construction began in 1995 on a Pharmacy, Chemistry, and Life Sciences complex adjacent to Bowman-Oddy Laboratories.

President Horton, architect Frank Gehry, and Toledo Museum of Art director David Steadman participate in the groundbreaking for the Center for Visual Arts in 1991. The building, attached to the museum, houses the university's art classes.

Some new programs were added to the curriculum, including a master’s degree in liberal studies, a women’s studies program, a Ph.D. in manufacturing management, and a Ph.D. in bioengineering. But at the same time, some long-standing doctoral programs were threatened when the Ohio Board of Regents sought to reduce the cost of graduate education in the state.

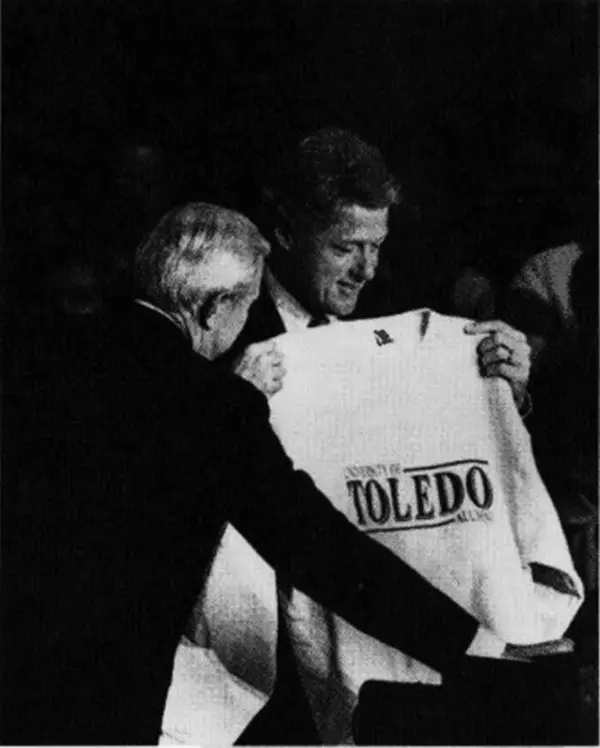

Future U.S. President Bill Clinton visited UT while on the campaign trail in 1992. (Photo by Liz Brandt)

Some of the most significant growth in the 1990s was not in buildings or academic programs, but in technology. The university joined OhioLINK, a statewide library network, in 1994. The network allows UT students to access and borrow books from all other member institutions throughout the state and utilize a wide array of research services. Computer labs and hook-ups in dormitories and offices provide Internet access to many students and most faculty. Technological improvements allow students to register for classes and check their grades by phone. The university established a homepage on the World Wide Web. Such innovations are certain to continue throughout the decade.

The first efforts in Carlson Library's automation project required that each book in the library's holdings have a barcode attached. President Horton showed his support for the project in 1991 . (Photo by Liz Brandt.)

But despite strategic planning and important improvements in physical spaces and technology, many challenges remain. State support for higher education must compete with other government demands like prisons and primary and secondary education. An improving economy in northwest Ohio and the growth of other institutions of higher learning in the area has produced competition for a declining pool of students. This competitive environment forced UT to take a close look at how it provided services to students and find better ways to attract and keep students. One major change is a switch from the 20-year old quarter system to semesters to allow for more cooperative programs with other universities.

U. S. Representative Marcy Kaptur receives an honorary degree from President Horton at the December 1993 commencement ceremony. (Photo by Liz Brandt)

On June 11, 1994, Kimberly Urban received the 100, 000th degree awarded by UT. (Photo by Bill Hartough)

Critics of higher education, who became more numerous and vocal in the 1980s, continue unabated in the 1990s. Government leaders, the press, and ordinary citizens have questioned the size, cost, politics, and goals of higher education. UT was not spared such criticism. Faculty members who felt they did not have a voice in university affairs voted in 1992 for collective bargaining representation by the American Association of University Professors. This has further strained the relationship between the administration and the faculty as each assumed new and often adversarial roles.

President Horton signs each of the diplomas handed out at commencement, 1993.

But a program undertaken jointly by Dr. Horton and the Faculty Senate in 1997 seeks to bring representatives from all sectors of the university community together in a series of discussions focused around the central challenges of higher education in the 1990s and beyond. From these discussions may come the themes that will shape the next 125 years of University of Toledo history.

Construction progresses on the new Pharmacy, Chemistry, and Life Sciences building, 1996.

Construction progresses on the new Pharmacy, Chemistry, and Life Sciences building, 1996.