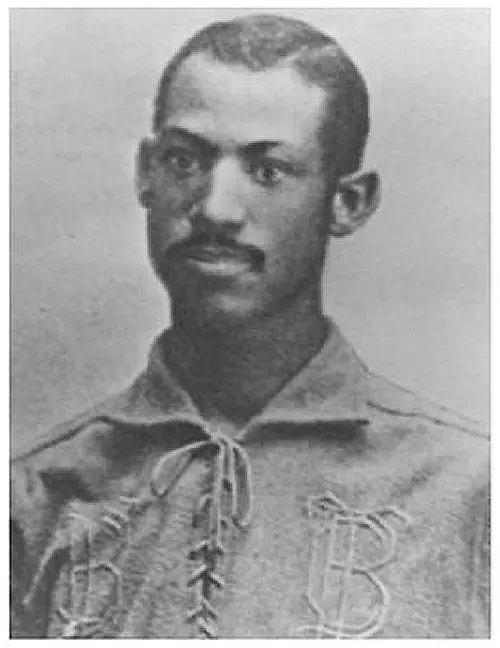

Moses Fleetwood Walker

Moses Fleetwood Walker's promising but all too short professional baseball career mirrors the experience of most of the great African American ballplayers before the Negro Leagues began in the early twentieth century. Walker was a gifted defensive catcher and adequate offensive player, but his career would be cut short by racism. Walker, well educated for a man of any race in the late 19th century, respond to this racism first with ambivalence, then with anger, and finally with prose. His seminal work, “Our Home Colony,” put him directly in line with the thoughts and words of future leader Marcus Garvey in his call for a separation of the races and a return of African Americans to Africa.

Formative Years

Moses Fleetwood Walker was born in Mt. Pleasant, Ohio in 1857. Mt. Pleasant, which was only a few miles from the Ohio River border with slave state West Virginia (then still part of Virginia), was founded by Quakers from Pennsylvania and North Carolina and was an important stop on the Underground Railroad for escaped slaves as well as a source of Quaker abolitionist propaganda before and during the Civil War. Early in Moses's life, the Walker family relocated to Steubenville, Ohio, a town with most of the same morals and social ideals as Mt. Pleasant. It was this environment, along with the emphasis on education instilled in the Walker children by their physician/minister father and educated mother, that would be the backdrop of Moses Fleetwood Walker’s youth.

The Walker home was active during the Civil War. Although the elder Moses was too young to serve in the various "Colored" regiments of the Union Army, he did open up his home to persons fleeing oppression in the South, and even eventually took in two children born into slavery.

In what would prove to be a fortuitous move, the elder Walker made the trek to Oberlin, Ohio to help reform a congregation at a local church. The younger Moses would later follow his father to Oberlin, enrolling in the college preparatory academy and later Oberlin College.

College and Early Professional Baseball

Fleet began his studies at Oberlin College in 1878. At Oberlin, Walker studied the traditional college preparatory courses, excelling in his first year and maintaining satisfactory marks for the rest of his time there. It was also during this time that Walker would have the chance to study with and from such intellectuals as Mary Church Terrell, George Herbert Mead, Henry Churchill King, and Ida Gibbs Hunt. When the college removed its ban on competitive inter-collegiate athletics, Walker quickly joined the newly formed baseball team.

In a game against the University of Michigan, Walker showed the skills that would allow him to later play professional baseball. In Michigan’s 9-2 victory, Walker finished a triple short of the cycle, and quickly caught the eye of the Michigan coaches.

Walker, along with his pregnant girlfriend Bella Taylor, pitcher Arthur Packard (son of Union general Jasper Packard), and brother Welday soon left for Ann Arbor to play for the Wolverines. While at Michigan, Walker enrolled in the Law School, but never finished his degree.

Collegiate athletics were still in their infancy in the late 19th century; as there were few rules that required players to maintain their amateur status, players routinely made money playing for local traveling company teams. Walker was no different, and while at Michigan, he made extra money playing baseball for traveling company teams in the Midwest. One of the first teams that Walker played for was the Cleveland-based White Sewing Machine Company. It was during his experiences playing for this team against Louisville that Walker had his first on-field run-in with racism.

In Louisville to play against the local Eclipse ballclub, Walker saw discrimination and segregation firsthand. Although Jim Crow laws had not yet come into being, Black Laws ruled Southern cities, which kept alive the South’s desire to separate the races. Before the game began, Louisville players balked at playing in a game against a black player, a reaction that Walker would see often in his professional career. Walker's manager relented and Walker did not play in the game, even after the starting catcher went down with an injury.

After an excellent season for the University of Michigan and a brief season playing in New Castle, PA, Fleet and Welday set out to finish school and follow in the professional footsteps of their father. Welday looked to complete his degree in homeopathic medicine while Fleet worked on his degree in law, at one time taking a brief position with a Steubenville law firm.

1883 was supposed to bring Walker back to either Ann Arbor or New Castle. Much to the surprise of both towns, Walker ended up in a new place, once again playing baseball: Toledo, Ohio.

Professional Baseball Career

Walker began his organized professional baseball career with the Toledo Blue Stockings of the newly created Northwestern League in 1883. The team, which was owned and managed by Cleveland Plain Dealer sportswriter William Voltz, offered Walker the chance to again play with Harlan Burkett, a fellow classmate and teammate from Oberlin.

Although Burkett would prove to not be up to the task of professional ball, Fleet was thriving defensively (while only hitting .251) in his new surroundings. Voltz soon returned to writing and Charlie Morton took over as manager of the club, when was in fifth place at the time. Morton turned the team around, quickly securing the top spot in the league and finishing two games above the Saginaw franchise. The 1883 season finished with the Blue Stockings winning the Northwest League championship.

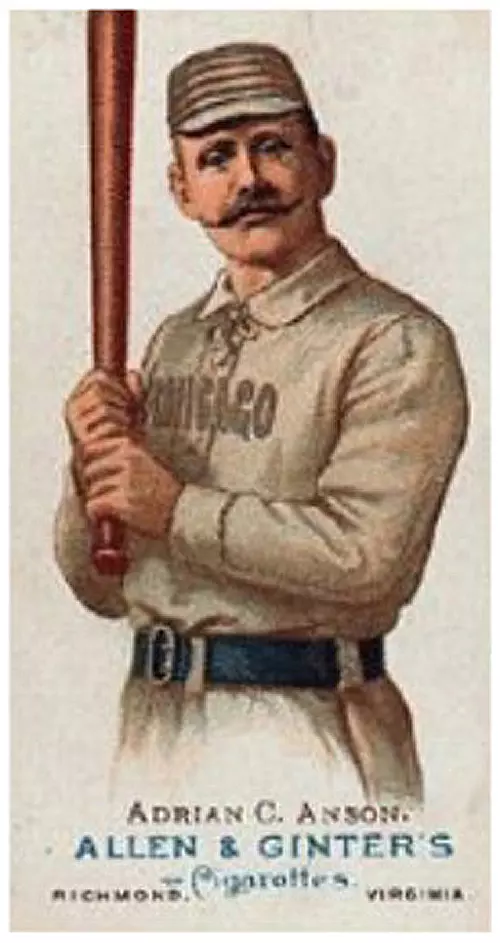

Life for Walker was about to get more complicated as the call to segregate baseball continued to gain traction. One of the major proponents of that idea was Cap Anson of the Chicago White Stockings.

Cap Anson Incident

After winning their first championship in 1883, the Blue Stockings were invited to play an exhibition game against the Chicago White Stockings. On August 10, the National League champs featured future Hall of Famer Cap Anson as a manager and player. At the time, Anson was in the prime of his career. Even though he had had an off season by his standards, he was still one of the most important figures in baseball.

When hearing that his White Stockings were scheduled to play against a team that featured an African American player, Anson (paraphrased to omit the racist language) stated that he would not set foot on the field if Walker played.

Although Walker was not scheduled to play his usual catcher position due to a hand injury (he did not use a glove), Toledo manager Charles Morton put Walker into the outfield after hearing Anson's racist comments. With the league's future still in economic limbo and fearing a loss of gate receipts, the Chicago ball club and Anson backed down and played the game anyway.

Although Morton forced Anson's hand and made him play against an African American player, Anson would have the final laugh, as he is considered by most to be a leading force in the gentleman's agreement that introduced the color barrier to baseball.