Our Toledo

Our Toledo

Exhibit Gallery

by Timothy Messer-Kruse, 2001

Program (cover) for the Toledo Girls Waltz

Program (cover) for the Toledo Girls Waltz

Every great city has its songs. Some, like Sinatra’s New York, New York, or Tony Bennett’s I Left My Heart in San Francisco evoke images that capture a city’s spirit. Some, like Woody Payne’s Sweet Home Chicago [*], become a city’s anthem, not so much for what they say about the place, than the way in which they say it. Songs have the power to capture the mood and soul of a city.

During the mid-nineteenth century, several songs and musical pieces were written about Toledo or places around it. There was the Toledo Girls Waltz, the Toledo Military Band March, the Bay View Waltz, and a tribute to one of Toledo's early amusement parks, Meet Me at White City. Many of these songs were published by the Woodward Music Company, a music publishing company that turned out scores of scores each month for decades. However, none of these songs really attempted to capture the city's spirit.

This changed near the turn-of-the-century. Over a dozen songs have been written about Toledo, Ohio and though none powerfully capture some universally recognized essence of the place, each of them reflects an interesting moment in the city’s history. From 1906 to 1992, balladeers have taken their turn at crafting the definitive city song. Though none achieved more than a minor fleeting fame in their own time, they serve well to chart the course of the city through the Twentieth century.

Progressive Toledo, 1906-1916

The first song describing Toledo, "We’re Strong for Toledo," was written by Joe Murphy in 1906. Murphy was the founder of the Citizen’s Ice Company and wrote the song for his barbershop singers, the Ice House Quartette. Murphy penned the original stanzas in a few evenings in the only key he knew. "We’re Strong for Toledo" reflected the vague optimistic spirit of Murphy’s age:

We’re Strong for ToledoWe’re strong for Toledo We’re strong for Toledo |

|

Murphy’s lyrics made few claims for the city he was born and raised in besides fair girls and square boys. This is its real strength. Unlike most of the succeeding tunes about Toledo that praise specific features, business opportunities, or institutions of the city, the generality of "We’re Strong" allowed it to suit the changing circumstances of the city.

Joe Murphy and his Ice Quartette

Joe Murphy and his Ice Quartette

Still, at the song’s core is a quaint view of the city as a harmonious unified whole. 1906, the year Murphy wrote his song, was perhaps the last that the idea of Toledo’s people all sharing the same interests could have been so boldly proclaimed. Toledo’s civic leaders had long praised its unusual climate of labor peace. Toledo, unlike similar mid-sized manufacturing and transportation centers, had largely escaped the large scale strikes and violence of the great railroad strikes of 1877, the eight-hour day strike wave of 1886, and the Pullman Strike of 1894. Relative to other Ohio cities, it lost few workdays to strikes in the first six years of the Twentieth century. But less than a year after Murphy finished "We’re Strong for Toledo," one of the city’s largest manufacturing concerns, the Pope Automobile Company, was shuttered by a massive strike. By 1909, the construction trade unions and an employers association were at each other’s throats, and a bomb was discovered on the site of a downtown building project. By World War One, Toledo would be an organizing center for the militant I.W.W. (Industrial Workers of the World) union in Ohio.

Murphy’s ice quartette grew from four to forty over the next twenty years. Invited to perform at the 1927 Rotary International World Convention in Belgium, "We’re Strong for Toledo" was sung across Europe and to millions of WRKO radio listeners upon the group’s return to New York.

Joe Murphy must have been stung when the city adopted a rival’s song for its official ballad in 1909.

"Our Toledo", by George G. Morrison and Eusebius W. Dodge.

Dodge, president of the American College of Music in Toledo, composed a more impressive melody and Morrison packed more specifics about the city into his lyrics. The Toledo City Council first heard it sung by a chorus of twenty-five voices in their chambers above the Valentine Theatre and swiftly moved to adopt it as the city’s official song.

"Our Toledo" speaks more directly to that era’s Toledo’s Progressive politics and self-image:

Our ToledoToledo on Lake Erie Crowned, Toledo is the fairest A home of welcome and of cheer, Imperial Toledo leads, |

Clearly an optimistic song, "Our Toledo" did not merely boost the city but expressed some principles as well. It clearly echoed many of the concerns of the years just prior to World War One: stanzas spoke of justice, high ideals, meeting the people’s needs, the march of the commerce of the nation and preserving a happy, welcoming and cheerful domestic home. With Brand Whitlock as mayor, a man of letters who inherited Samuel "Golden Rule" Jones’ mantle of reform, claiming such a high moral character for their city did not seem to them presumptuous.

"Our Toledo" spoke confidently of the city’s status and growth. It did not have the whiff of desperation or fear that lingered around later songs. From the perspective of 1909, the city’s future did seem assured. Toledo continued to lead Ohio in percentage growth in the number of its factories, wage earners, and the level of its wages. In 1905 the editors of the Toledo News-Bee declared, "Thrifty, thriving, hustling Toledo, the gateway to the Northwest, has an industrial future radiant with promise to the investing manufacturer and to the wage earner." (July 10, 1905) So fast was the pace of population growth that by 1913, homeowners purchased lots and pitched tents while waiting for their turn for contractors to begin work. (Blade, July 11, 1913) As the city council voted "Our Toledo" the city’s official song it could look out its windows at the rising skyline — Tiedtke’s Department Store new six-story structure was just reaching completion down the block; plans were just announced for an even larger LaSalle and Koch store to be built the following year; a few miles north, the new home of the Toledo Mud Hens, Swayne Field, began its first season; the first of many expansions of the old Pope Automobile factory was being planned by its new owner, John North Willys; the first wireless radio broadcasts moved out from the city.

By 1916, there were many reasons for this optimistic spirit to dim. Chief among them was the growing conflagration spreading across Europe. Still, another Toledo resident, J.W. Crook, borrowed the wartime tune of "Tramp, Tramp, the Boys are Marching" and rewrote the lyrics into the "Toledo Song":

Toledo SongOn the banks of the Maumee |

|

Crook’s "Toledo Song," if nothing else, was certainly the most detailed of all Toledo tunes up to this point. Less a song than a business prospectus, it nevertheless does carry a few interesting references: it remembers mayor Samuel "Golden Rule" Jones who died in office over a decade before, it makes a patriotic appeal to service in wartime, it mentions Toledo’s natural advantages, though Crook may have bent the truth a bit with his "winters warm and summers cool" claim.

Most interestingly it notes a few of the city’s deficiencies as well as its strengths (something that few later songs could bear to do — only an optimistic generation can graciously admit its flaws). In stanza four, Crook notes that the city lacks a decent downtown bridge across the broad Maumee that would connect the East and West sides of town; that the city was one of the few with a population over 100,000 in the country that did not have its own city hall (city court, council, and mayor’s chambers and offices occupied the top two stories of a downtown theatre); and the baseball team didn’t amount to much until Casey Stengel arrived to manage it in 1926.

Toledo’s Roaring Twenties and Depressing Thirties

After the war and its year or two of uncertainty and economic dislocation, Toledo benefited greatly from the rapid expansion of the automobile industry and consumer spending generally. However, the local economy began to shift away from a diverse manufacturing city of hundreds of small and medium sized factories to becoming one dotted with a few massive corporate employers. Toledo’s glass corporations consolidated and grew quickly, with Libby-Owens-Ford’s nearby Rossford plate glass plant becoming one of the largest in the world. Willys-Overland expanded enormously to eventually account for over forty percent of the entire area’s payroll by the middle of the decade.

Smaller businessmen saw opportunity, but were also threatened by the increasing power of the few. Realtors and developers responded to a time of easy credit and steady population growth to plot thousands of house lots and scores of new subdivisions. Together these interests grew more aggressive in advertising the city and attempting to lure people and companies to relocate to Toledo. The songs of the 1920’s reflect this energy, a drive that would soon become urgency.

In 1922, Paul W. Austin, who composed musicals while a student at Ohio State, wrote "Talk Toledo (Boost Toledo)", a lyric without surviving melody. It went:

Talk Toledo!Talk Toledo!Talk Toledo any time or where, On the shores of old Lake Erie. We will stay right there, In the winter or the summer Sunshine, rain or snow, We’re with you, behind you, in all you do– To-le-do O-hi-o |

Boost Toledo! |

Austin is a bit more insistent that his listeners "boost Toledo," but unlike those who would follow, Austin doesn’t promote any particular feature of Toledo, just that it is "a great town." Austin’s gentle loyalty to his city is in keeping with Toledo’s optimistic and booming outlook during the 1920s. Perhaps Austin’s was the last age in which the city could be "boosted" without making any particular claims for it, without shouting its features. His was a confident time and the confident don’t need to extol their virtues, they merely carry them.

Confidence was the city’s spirit in the 1920s. The automobile industry boomed and Toledo became known as "Little Detroit" for its increasing dependence on the sale of cars. Real estate developers mapped out enough lots to house a population of several million. Toledo banks competed for the prestige of building the highest edifice - Toledo Trust succeeded in claiming second tallest in Ohio for a time — and half a dozen large hotels opened for business downtown.

Of course, all this changed quite suddenly between the spring of 1929 and the summer of 1931. First Willys Overland laid off thousands. Then real estate prices cooled and the building of subdivisions ended. The real shock came in the summer of 1931 when all major banks in Toledo shut their doors, freezing the savings of tens of thousands of people and pushing hundreds of businesses into bankruptcy. Soon the city itself was bankrupt and began paying public employees in I.O.U.’s, which local merchants honored at a fraction of their face value.

No songs were written about Toledo in its hard times. No one cared to sing about its weather, or trees, or its loyal people. It would be thirty-five years before anyone ventured to make a musical claim for their city again.

Postwar Hopes

It wasn’t until the mid-1940s and the militarization of the economy during World War Two that Toledo’s employment rolls, wages, or population began to recover. Many feared that the wartime recover would prove to be just that, a feature of war and not the peace that would follow. But by the early 1950s, Toledo’s economy was growing again and the old songs of boosterism were taken off the shelf, dusted off, and put to work again.

In 1950, the Chamber of Commerce took out a copyright on Joe Murphy’s old "We’re Strong for Toledo" song and began printing the score. Though the businessmen of Toledo were nostalgic for the locally famous tune, to the Chamber, Murphy’s lyrics were apparently not an adequate advertisement for the city. The Chamber had Marilou Dawn compose some added verses that spoke to an age of American business triumphant:

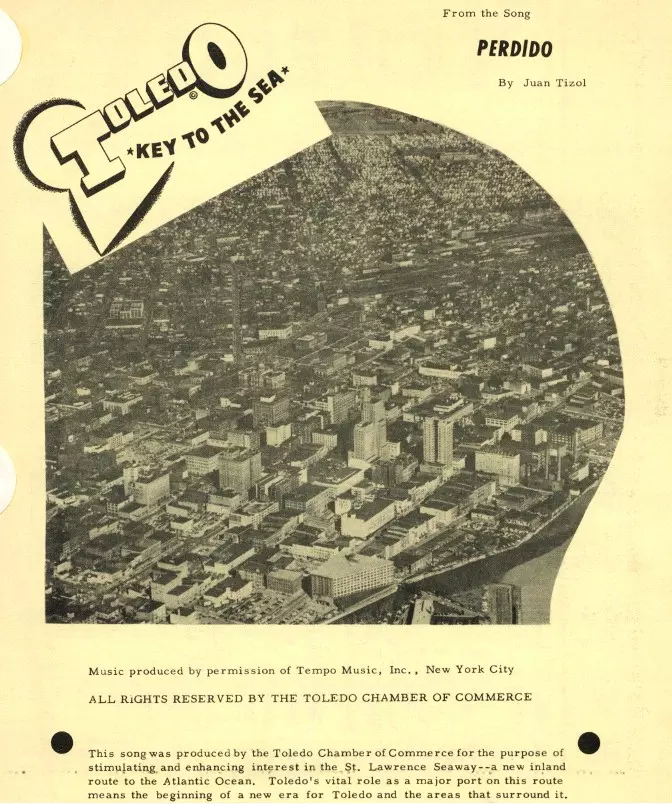

Building on its newfound interest in the musical arts, the Chamber of Commerce next commissioned a song to call attention to the opening of the St. Lawrence Seaway and Toledo’s place in the trade of the Great Lakes. For this duty the Chamber tapped Edmund Wheelden, Jr., member of the Chamber’s public relations department and a local factory president, who penned "Toledo, Our Future’s Terrific" set to a tune that Duke Ellington popularized, Perdido.

Though recordings were made of "Toledo, Our Future’s Terrific," by the El Myers Quintet, a local band, none seem to have survived the ravages of time.

The 1950s proved to be the rival of the 1920s in its song output. In 1957, just a year after the release of "Toledo, Our Future’s Terrific," Walter Schwartz, an employee of the City’s Harbor and Bridges department, revised the lyrics to "We’re Strong for Toledo" to give them a nautical twist. Gathering together a group of friends who had never sung together—Marvin Stimpfle, Carl Murphy, and George Yeats,—Schwartz recorded the song and dubbed his group the Channel Markers. Schwartz’s version was:

The Port SongWe’re strong for Toledo |

Listen to audio

Walter Schwartz, The Port Song, 1958. Music used with the permission of BMI Music |

Most notably about Schwartz’s Port Song, was his use of ambient sounds. The song begins with a blast from the horn of a passing freighter and continues with a faint sound of lapping waves beneath the chorus.

The capstone to this era of musical promotion came in 1965, when the Toledo Area Development Corporation commissioned "Let’s Expand Toledo’s Future." Set to the tune of "I’ve Been Working on the Railroad," this song stripped away all the distracting cant about seasons, trees, and loyal people to attain a purity of form seldom rivaled:

Let’s Expand Toledo’s FutureLet’s expand Toledo’s futureWith salesmanship today. Let’s expand Toledo’s future The T.A.D.C. way. The days of gloom are gone forever. Our town has been reborn. Can’t you hear our people shouting, Toledo, Blow your horn. Toledo won’t you blow, Toledo won’t you blow, Toledo won’t you blow your ho-o-orn! Toledo won’t you blow, Toledo won’t you blow, Toledo won’t you blow your horn. |

Someone’s in there pitchin’ Toledo.

|

This song’s final line, in its stark honesty, may never be rivaled within this category of expression. That the song did not last was not its own fault, but that of timing. Within a handful of years of its appearance, the industrial economy of the entire northeastern United States began to weaken and shift. Toledo sat astride the so-called "rust belt" and suffered a wave of plant closings, some of which, like that of Toledo Scale, seemed to steal away a piece of the city’s identity.

A Musical Identity Crisis

In the midst of what was a very difficult time for the city, the city received a musical boost in March of 1972. Joe Murphy’s "We’re Strong for Toledo" was borrowed for promotional use by the Libbey-Owens-Ford Company, the producer that provided three-quarters of General Motor’s auto-glass. For the first time since the early 1920s, Murphy’s song was heard on a nationwide radio network, this time during Walter Cronkite and Howard K. Smith’s nightly news broadcast carried on 700 radio stations. Once again, "We’re Strong for Toledo" was altered to suit commercial purposes:

We’re strong for ToledoWe’re strong for ToledoT-O-L-E-D-O The girls are the fairest, The boys are the squarest Of any old town that I know. |

We’re strong for Toledo |

The city reveled in its national exposure. Ten thousand buttons were distributed to Toledoans bearing the slogan, "We’re Strong for Toledo." But later that same month, just as "We’re Strong for Toledo" was piped into millions of homes, an unkempt, bespectacled folk singer single-handedly turned sixty years of musical boosterism into a comical irony. John Denver appeared on the Tonight Show and sang a song of savage ridicule, "Saturday Night in Toledo."

It was a song originally composed by Randy Sparks, founder of the New Christy Minstrels, in 1968 and which Denver had performed on and off again at various performances for about a year. Few but Denver’s fans knew of the song until Denver debuted it on Johnny Carson’s late night television show before an estimated audience of 30 million viewers.

In a weird way, "Saturday Night in Toledo" and "We’re Strong for Toledo" actually share parallel themes. Murphy’s song makes three very simple claims. That the people of Toledo are united in its progress, that Toledo’s female population is attractive and its male population is honest. "Saturday Night" shares these themes, only in mirror image. Toledoans, says Sparks and Denver, are disunited to the point of invisibility:

| Ah, but after the sunset, the dusk and the twilight, Shadows of night start to fall. They roll back the sidewalks Precisely at ten, And people who live there are not seen again. |

Where "We’re Strong" claimed that its "girls are the fairest" Sparks/Denver closed with:

| So live and let live — let this Be our motto, Let’s let the sleeping dogs lie. And here’s to the dogs of Toledo, Ohio Ladies, we bid you good-by. |

In the most eerie parallel, both songs claim Toledo is "square." But "square" in Murphy’s day meant something very different from what square meant to Denver’s generation. When Murphy composed his song "square" meant someone who was just, fair, honest, clear, direct, and straightforward. By the 1960s, "square" meant someone who was old-fashioned, unsophisticated and conservative. Of course, by 1972, fewer people were willing to trade stylish sophistication for dowdy integrity.

In spite of the bruising that Denver had given the city’s image, when he arrived to perform at the city’s Sports Arena in November of 1973 the city’s boosters greeted him with a warm welcome. The Toledo Area Convention Bureau made Denver an honorary member, dignitaries presented him with a music box that played "We’re Strong for Toledo," Toledo Scale cuff links, and a t-shirt that said, "John Denver is Strong for Toledo." Later that night, a Saturday night, Denver sang his now notorious song before a laughing, sell-out crowd.

The sting of that song lingered for the better part of a decade and was still evident in the mid-1980s when Randy Sparks, the song’s creator, was asked to sing it a final time on the city’s waterfront. After Sparks sang a six-foot tall copy of the song’s lyrics were lowered into a coffin and ceremonially buried. Sparks then apologized for the song to Toledo’s mayor, Donna Owens, and she observed, "When I think back at that song and all the interest and all the . . . all the . . . aggravation that it created in our city, I think it was a blessing in disguise, because needless to say we have a story to tell now."

|

Sparks was then commissioned to write what yet another song about Toledo, this time one that sang about its virtues. His first attempt was rejected:

|

Holy Toledo, Sunday Morning, We know how to party now, Lord, |

This song, while catchy, was both too closely tied to his "Saturday Night" song and too impious for many Toledoans. Sparks tried again, this time with a tune that was accepted and promoted by the Chamber of Commerce, "I Want My Maumee." This was a song that, except for its corny refrain, was a throwback to the promotionalism of the 1950s with its checklist of references to local institutions and qualities:

I want my MaumeeI want my Maumee I want my Maumee |

So lay me down to sleep

|

In spite of its sexual innuendo, its dangerous notion of recalling a Jeep, and its perpetuation of the memory of his earlier song, for this effort Randy Sparks was given the key to the city and named the official "Musical Ambassador" of Toledo, Ohio. Perhaps it wasn’t the song that was important, but simply the fact that the culprit had been made to atone for his crime, the blasphemer for his apostasy. The author of "Saturday Night" had now come full circle and engaged in the musical boosterism that his original song had so deftly destroyed.

Timothy Messer-Kruse

University of Toledo

Nov. 2001

* Note [3/19/2015]: This is a misattribution to Woody Payne, as John Hichman points out that the original creator of the song is Robert Johnson. See Jim Messman, "Records on the Wall Builds Artists' Lost Royalties," in Billboard (August 3, 2002): 33. Toledo's Attic would like to thank Mr. Thomas Tharp for pointing out this inaccuracy and would like to issue an apology for any inconvenience it may have caused our readers.

Sheet Music (PDF files)

A Collection of Toledo Songs (MP3 files)

The MP3 files of the following songs are accessibile below. All music used with the permission of BMI Music.

|

Joe Murphy, We're Strong for Toledo, circa 1950's Listen to audio

Joe Murphy, We're Strong for Toledo, with references to Saturday Night in Toledo, circa 1972-73 Listen to audio

Walter Schwartz, The Port Song, 1958 Listen to audio

Randy Sparks, I Want My Maumee, circa 1980s Listen to audio

|

Publications, News clippings, and Advertisements

The Toledo City Journal, February 1, 1947 [PDF Link]

"The Story of the City Seal," The Toledo City Journal, Vol. XXI, No. 7, February 15, 1936 [PDF Link]

News clippings, and Advertisements (slides)